It’s a hard country on man; it’s hard. Eight miles of the sweat of his body washed up outen the Lord’s earth, where the Lord Himself told him to put it. Nowhere in this sinful world can a honest, hard-working man profit. It takes them that runs the stores in the towns, doing no sweating, living off of them that sweats. It ain’t the hard-working man, the farmer. Sometimes I wonder why ye keep at it. It’s because there is a reward for us above, where they can’t take their motors and such. Every man will be equal there and it will be taken from them that have and give to them that have not by the Lord.

I am the chosen of the Lord, for who He loveth, so doeth He chastiseth. But I be durn if He don’t take some curious ways to show it, seems like.

Anse Bundren

William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying was first publish in 1930. He started writing book the day after the stock market crashed in 1929. He wrote it whilst working the night shift at a power plant. He claimed to have finished it in a little over 6 weeks:

Got a job rolling coal in a power plant. Found the sound of the dynamo very conducive to literature. Wrote As I Lay Dying in a coal bunker beside the dynamo between working spells on the night shift. Finished it in six weeks. Never changed a word. If I ever got rich, I am going to buy a dynamo and put it in my house. I think that would make writing easier.

Faulkner was notorious for not taking interviews too seriously: in his mind, he was an artist, and his contribution to the world was his art, not his interviews. My favourite Faulkner interview line occurred when being asked about another book of his, the notoriously difficult Absalom, Absalom!

Interviewer: Some people say they can’t understand your writing, even after they read it two or three times. What approach would you suggest for them?

Faulkner: Read it a fourth time.

Almost all of Faulkner’s work is set in the fictional county of Yoknapatawpha, Mississippi, itself inspired by his home county of Lafayette. He is a writer firmly of his place. I think that’s what draws me to his work. When he writes of land, of the country, and of its people, it is deep and intimate. It is not the vague poetic emptiness that passes for “nature writing” today.

As I Lay Dying tells the story of the Bundren family. It centres about the death of the matriarch of the family, Addie Bundren. The novel begins with Addie on death’s door. It is her dying wish to be buried with her ancestors in Jefferson. This is no small request. Jefferson is far. Her dead body, entombed in the coffin built by her son Cash, will have to be carried for days to reach the town’s cemetery. The family endures horrors of biblical proportions to honour their mother.

The Bundrens, like the Joad family of Steinbeck, and like Faulkner himself, are “poor whites”: sharecroppers that do not own the land they live and work on. By some estimates, this was the case for nearly 80% of farm labourers in Mississippi at the time. Their poverty is palpable. Yet despite this poverty, or perhaps because of it, the Bundrens are an intensely proud and autarkic family. “We wouldn’t be beholden to no man, God knows.” Reading this book, nearly 100 years hence, there is a strange, hard-to-articulate feeling of otherness to the Bundrens. Their values, their actions, their pride feel out of place, even in the novel itself, let alone against the backdrop of today’s world. Their world is peasant world, in the literal sense of pays-ent: someone of the country, of the land. Their values, priorities, concerns, rivalries, desires are shaped by the uniqueness of the place that they inhabit. It is tremendously disorientating to read from the vantage point of a gentrified, commodified rural England.

None of this is to romanticise. In the words of Wendell Berry: “It is the rule that we often romanticise what we have first despised.” Faulkner has a profound respect for his characters. Despite their intense poverty, they are not “backwards”, or “stupid”, or “simple country folk” or any other such insult. They are articulate, and insightful.

Thiers is a culture centred about land, a deep Christian faith, an intimacy with and reverence of death. In the first third of the novel, whilst Addie is still alive, there is a constant background noise of a handsaw. Cash, the eldest son, unique amongst the family for his carpentry skills, is crafting his mother’s coffin. He labour meticulously for days, whilst Addie lays dying, looking out the window, watching. After every plank is cut to Cash’s approval, he holds it up for his mother to see. Proud and resolute, confident in his role at his mother’s death. Their attitude feels harrowing and morbid.

Personally speaking, it was these three themes — land, God, and death — that distinguished their world most markedly from our (my) own, and so felt most jarring to read. Obviously, there are other themes to the novel: it’s also a novel about family, and its rivalries, about hardship and overcoming, and, to take a line from Faulkner’s Nobel prize acceptance speech, about “man’s inexhaustible capacity for compassion and sacrifice and endurance”. Yet, it was the Bundrens’ defiance and otherness that felt most compelling, their sense of pride and moral rectitude. And this defiance and otherness finds its source in their land, their faith, and the weight of death.

To give one small example, this quote is from a chapter of Anse Bundren, the husband of Addie. His wife is not yet dead, and the family have not yet begun their journey. He is cursing his God-given fate in living so close to a road:

I told Addie it wasn’t any luck living on a road when it come by here, and she said, for the world like a woman, “Get up and move, then.” But I told her it wasn’t no luck in it, because the Lord put roads for travelling: why He laid them down flat on the earth. When He aims for something to be always a-moving. He makes it long ways, like a road or a horse or a wagon, but when He aims for something to stay put. He makes it up-and-down ways, like a tree or a man. And so he never aimed for folks to live on a road, because which gets there first, I says, the road or the house? Did you ever know Him to set a road down by a house? I says. No you never, I says, because it’s always men can’t rest till they gets the house set where everybody that passes in a wagon can spit in the doorway, keeping the folks restless and wanting to get up and go somewheres else when He aimed for them to stay put like a tree or a stand of corn. Because if He’d a aimed for man to be always a-moving and going somewheres else, wouldn’t He a put him longways on his belly, like a snake? It stands to reason He would.

His faith, and his being of a place, are abundantly clear. God is witness, the giver of life, the ultimate judge. The seriousness of these characters, and the respect that Faulkner affords them, is also abundantly clear. These are not trivial struggles.

Each chapter is written from the perspective of a different character, using a steam-of-consciousness style that Faulkner, like his contemporaries Joyce and Woolf, helped pioneer. We see the world, if only momentarily, as Faulkner’s characters do: when the writing is at its best, there is no distance. Importantly, there is no impersonal narrator, no abstracted “God’s-eye-view”. Neither is there a sentimental diarist, with impeccable memory of events long since passed. In Faulkner’s world, the events do not exist outside of the characters. The plot is driven forwards only through the eyes and the minds of those living it.

The immediacy of this narrative style creates a fragmentation. Each chapter is from the perspective of a different character. Without a centralised narrator, there is no centralised story. Time and place jump about from character to character; the truth is owned by no-one. Multiple tellings overlap and contradict one-another. This disunity reinforces the strangeness of the Bundrens: hidden amongst the competing contradicting perspectives is a sense of dis-ease. The sense that something is lurking, something that cannot be said, something that we are not supposed to know. In the gaps between narratives has Faulkner hidden their secret.

Faulkner was heavily influence by Homer’s Odyssey in writing As I Lay Dying. Its name is taken directly from the text. The most obvious influence of the Odyssey is that of the epic journey. Odysseus’ ten-year return to Troy is mirrored in the ten days it takes to return Addie to Jefferson. And their journey is similarly apocalyptic.

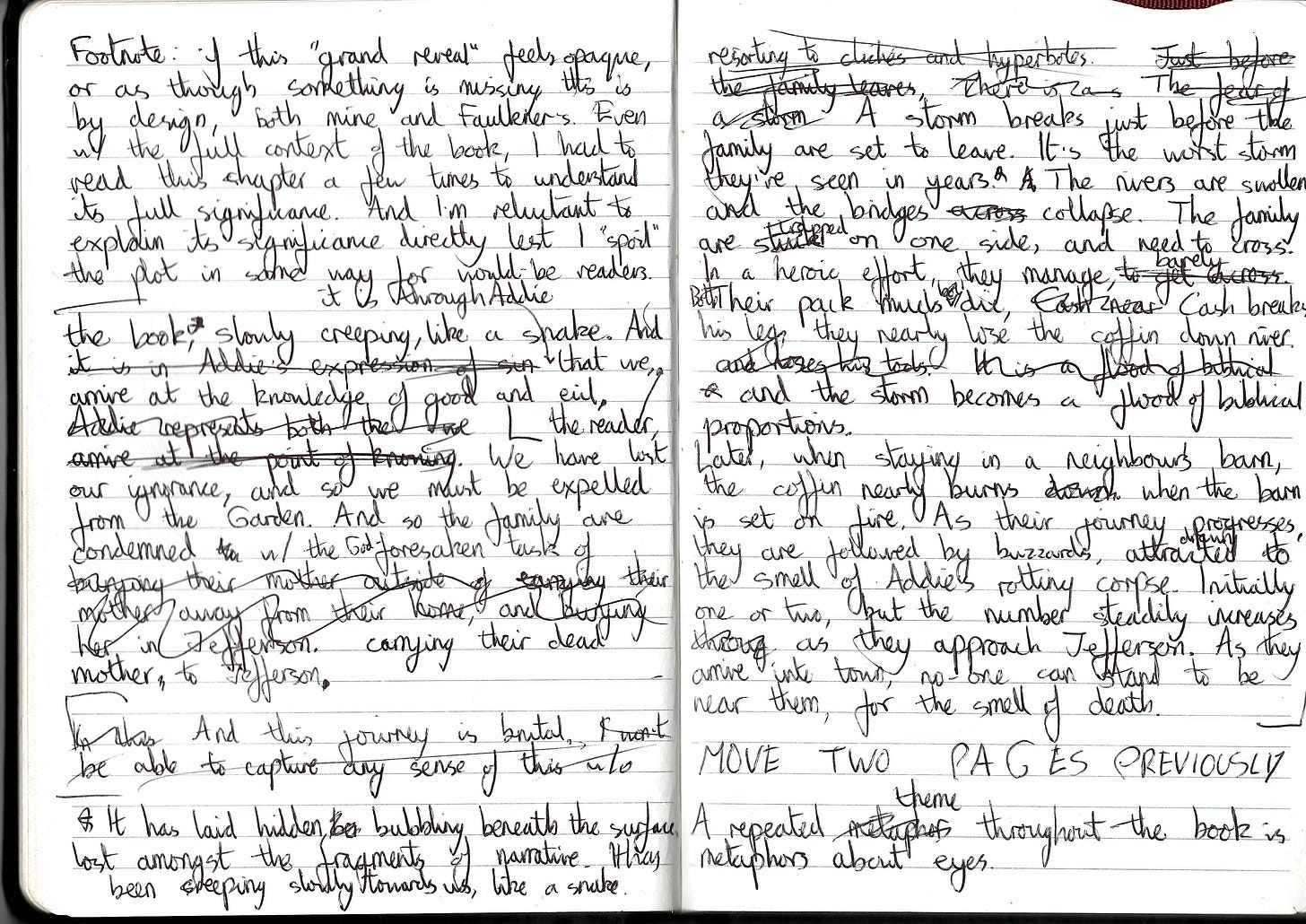

A storm breaks just before the family are set to leave. It’s the worst storm in living memory, and the storm becomes a flood of biblical proportions. The rivers are swollen, and the bridges collapse. They are trapped on one side, and need to cross. In a heroic effort, of Odyssean proportions, they manage to cross, barely alive. Both their pack-mules die, Cash breaks his leg, they nearly lose the coffin down river. Later, when staying in a neighbour’s barn, the coffin nearly burns when the barn is set on fire. They begin to be followed by buzzards. Initially one or two, but the number increases. Near the journey’s end, they can no longer leave the coffin, for fear of the buzzards attacking it. As they arrive into town, no-one can stand to be near the family, for the putrid smell of death.

A more subtle nod to the Greek epic tradition is the use of the voice of the dead. Despite hearing so much about this woman, there is only one chapter where Addie Bundren speaks for herself. It occurs immediately after her coffin is nearly lost down river. The narrative breaks, and we momentarily inhabit a timeless place. It’s Faulkner’s brilliance that allows this to work, that makes it feel right to read the voice of the dead. Addie’s chapter is some of the best pages of fiction I’ve read in a long time. To give the first two paragraphs:

In the afternoon when school was out and the last one had left with his little dirty snuffling nose, instead of going home I would go down the hill to the spring where I could be quiet and hate them. It would be quiet there then, with the water bubbling up and away and the sun slanting quiet in the trees and the quiet smelling of damp and rotting leaves and new earth; especially in the early spring, for it was worst then.

I could just remember how my father used to say that the reason for living was to get ready to stay dead a long time. And when I would have to look at them day after day, each with his and her secret and selfish thought, and blood strange to each other blood and strange to mine, and think that this seemed to be the only way I could get ready to stay dead, I would hate my father for having ever planted me. I would look forward to the times when they faulted, so I could whip them. And I would think with each blow of the switch: Now you are aware of me! Now I am something in your secret and selfish life, who have marked your blood with my own for ever and ever.

These opening words are so jarring to read because they reveal how ignorant we, as the reader, have been. Naively, we’re led to assume that the family undertakes such a sacrifice out of love and respect for their dead mother. The violence of Addie’s words shatters this. She reveals herself as cruel, almost evil, longing for moments where her children would falter, so that she could beat them. This journey is not motivated by the best of human emotions, but the worst.

So I took Anse. And when I knew that I had Cash, I knew that living was terrible and that this was the answer to it. That was when I learned that words are no good; that words don’t ever fit even what they are trying to say at. When he was born I knew that motherhood was invented by someone who had to have a word for it because the ones that had the children didn’t care whether there was a word for it or not. I knew that fear was invented by someone that had never had the fear; pride, who never had the pride. I knew that it had been, not that my aloneness had to be violated over and over each day, but that it had never been violated until Cash came. Not even by Anse in the nights.

He had a word, too. Love, he called it. But I had been used to words for a long time. I knew that that word was like the others: just a shape to fill a lack; that when the right time came, you wouldn’t need a word for that any more than for pride or fear.

For Addie, life is a curse, a heavy burden, and its purpose is to get ready to stay dead a long time. Despite how it sounds for modern readers, it is not a privilege to be “made of a place”, not a privilege to depend on land so intimately. It is the brute fact of her deeply impoverished life, and she hates her God for this. Addie’s hatred of her fate culminates as a rebellion against her family, and a rebellion against God.

I believed that I had found it. I believed that the reason was the duty to the alive, to the terrible blood, the red bitter flood boiling through the land. I would think of sin as I would think of the clothes we both wore in the world’s face, of the circumspection necessary because he was he and I was I; the sin the more utter and terrible since he was the instrument ordained by God who created the sin, to sanctify that sin He had created. While I waited for him in the woods, waiting for him before he saw me, I would think of him as dressed in sin. I would think of him as thinking of me as dressed also in sin, he the more beautiful since the garment which he had exchanged for sin was sanctified. I would think of the sin as garments which we would remove in order to shape and coerce the terrible blood to the forlorn echo of the dead word high in the air.

There is a feeling throughout the novel of some unspeakable truth at the heart of this family. Why must Addie be buried in Jefferson, with her own family? Why can’t she be buried with the Bundrens? And why is there so much hatred in this family? And why is it that they are so compelled to make this cursed journey?

That unspeakable truth is Addie’s act of rebellion against life. And so that which is unspeakable for the rest of the family can only be told by Addie herself, after her death1. It is through Addie’s rebellion against life, and so ultimately against God, that we as readers move from ignorance to knowledge. This is where Faulkner becomes explicitly religious in his imagery. This movement from ignorance to knowledge, motivated by a rebellion against God, is the Christian Fall. And it is the knowledge of sins of Addie, slowly creeping towards us like a snake, that has created this transformation. Symbolically, it is through Addie’s rebellion that the family are expelled from the Garden, from the only home they’ve ever known, and are condemned with the God-forsaken task of burying their dead mother in Jefferson.

A repeated theme throughout the book is metaphors of eyes. Jewel has “eyes like wood, set into his wooden face.” Darl has “eyes full of the land, dug out of his skull and the holes filled with distance beyond the land.” Anse has “eyes like piece of burnt-out cinder”. Addie, on her deathbed, has “eyes like two candles when you watch the, gutter down into the sockets of iron candle sticks.”

It’s bloody beautiful writing. It’s also another nod to the Odyssey. As I said earlier, the title is a direct quote from the text. The full line reads: “As I lay dying, the woman with the dog’s eyes would not close my eyes as I descended into Hades.” It’s spoken by Agamemnon, in Hades, telling of how he was murdered by his wife’s lover. The woman with the dog’s eyes is his wife, Clytemnestra. The reference to one of the most infamous murders in classical myth sets the precedence for the complex, hateful, and sometime violent rivalries amongst the Bundrens. This particular reference, with eyes that would not be closed, also makes explicit the link between seeing and knowledge: to have eyes wide open is to act without ignorance. It is Addie, with her eyes like “the sockets of iron candle sticks”, that acts in full knowledge of her sin. Her eyes are open to the fallenness of the world, and the harshness and suffering that this brings.

And this was the principal impression left on me by this brilliant book: the harshness of their lives. These people are brutally poor. Their life is not easy. They carry their mother’s corpse for ten days, to fulfil her dying wish, because they have no choice to do otherwise. They are strange, and hateful, and somehow alien to everywhere that is not their small world. For someone like myself, with a nostalgia for a living rural culture, situated amongst today’s rural gentrification, who takes pride in being of a place, with a conviction that a life close to land is one of meaning, that there may be wisdom found in how we used to live, for someone like myself this book cuts through a lot of bullshit. It forces me out of convenient generalisations and limp apologies. I’m quick to claim — in a comfortable, overtly politicised way — that land is the original source of all wealth, and that everything else is a paper promise; I’m perhaps slower to acknowledge that that wealth is not by definition abundant. Theirs is a life where death and God are at the centre of all things, not through enlightened choice, but because it is too brutal for it to be otherwise.

This book is brilliant, so brilliant that I feel compelled to write this essay. It’s the sort of book that makes me grateful for fiction, and grateful for writing in general. It’s so good that it makes me wonder why I bother writing anything at all, because I’ll never say anything as well or as beautifully as Faulkner does. But alas, I must try – if nothing else, out of respect for “man’s inexhaustible capacity for compassion and sacrifice and endurance”.

If this “grand reveal” feels opaque, feels as though something is missing, this is by design, both mine and Faulkner’s. Even with the full context of the book, I had to read this chapter a few times to understand its full significance. And I’m loath to explain its significance fully, lest I “spoil” the plot in some way for would-be readers.