My brother and I recently saw John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath at the National Theatre. We managed to find cheap, last-minute tickets. I’m slow to say that I enjoyed it, in much the same way that I’m slow to say that I enjoyed the book: it’s brutal, moving, desperate, hopeful, and more, in one long story. Steinbeck famously wrote that his objective in writing was to “rip a reader’s nerves to rag”. The play certainly delivered.

For those who have never read The Grapes of Wrath, those whose experience of Steinbeck is limited to a tedious and tired GCSE-English analysis of Of Mice And Men, limited to a rehashing of George and Lenny as the thwarted American dream, limited to questions on what the character of Curley and his vaselined-glove represent, questions of freedom versus slavery — for those of you, first and foremost, I’m sorry; Steinbeck is great, and this experience does him an utter disservice.

Secondly, let me try to summarise.

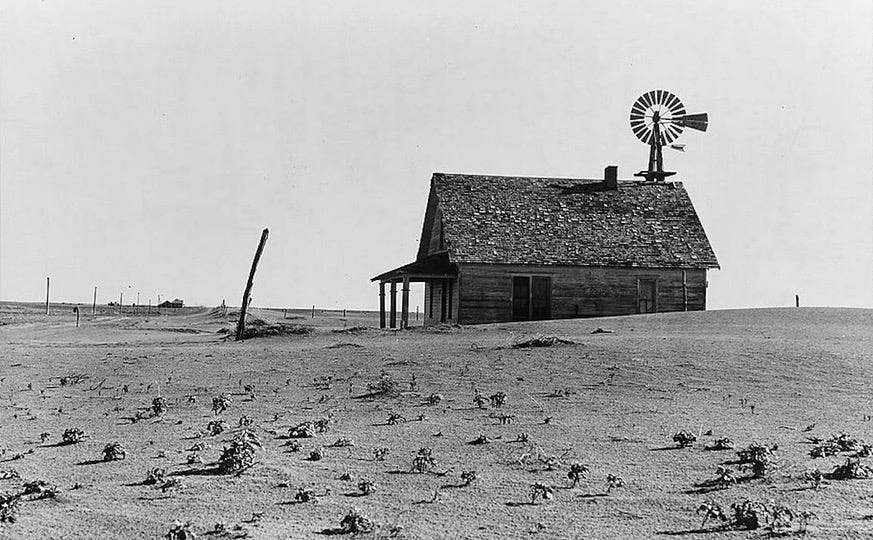

The Grapes of Wrath tells the story of the Joad family, as they are forced to migrate from their home in Oklahoma. The backdrop of the novel is the dustbowl of the 1930s, which ravaged the ecology and farmland of the prairies of the USA and Canada. Successive years of drought and bad land management, leads to successive years of crop failures, leads to a forced eviction by the banks. And so the Joad family head to California in a desperate search for work. The journey is devastating for the family, even fatal for some. Throughout their journey, California is the singular point of hope. On their arrival, the promise of California is utterly broken. There is no work. The family, or what remains, is forced to settle in migrant camps, where they’re treated with scorn and contempt by almost everyone. They move from town to town in a fruitless search for work. (No pun intended.) The novel builds devastation upon devastation, until the eventual climax. Yet, amongst this devastation, Steinbeck managed to create a profoundly human story, redemptive and dignified.

Whilst the Joad family didn’t exist in an historical sense, their story is true, and really was the experience of thousands of Americans during the 30s. There is a scene early in the novel where a group of children cower in fear at a tractor. It’s the first they’ve ever seen, and this machine is not to be trusted. Steinbeck was writing at the cusp of the machine age, the first unfurling of industrial agriculture. This machine age, and the logic that underwrites it, remains the logic that governs agriculture today. The details have changed, no doubt, as our technology has changed. But its essence remains, and has become total. Even the self-styled dissidents, such as myself, bear its weight, operating in the negative-space of its logic. Farmer’s markets came after supermarkets: first there were simply markets. But before I get too abstract, let me try to ground this essay in some of the best of what Steinbeck’s writing can offer:

The houses were left vacant on the land, and the land was vacant because of this. Only the tractor sheds of corrugated iron, silver and gleaming, were alive; and they were alive with metal and gasoline and oil, the disks of the plows shining. The tractors had lights shining, for there is no day and night for a tractor and the disks turn the earth in the darkness and they glitter in the daylight. And when a horse stops work and goes into the barn there is a life and a vitality left, there is a breathing and a warmth, and the feet shift on the straw, and the jaws clamp on the hay, and the ears and the eyes are alive. There is a warmth of life in the barn, and the heat and smell of life. But when the motor of a tractor stops, it is as dead as the ore it came from. The heat goes out of it like the living heat that leaves a corpse. Then the corrugated iron doors are closed and the tractor man drives home to town, perhaps twenty miles away, and he need not come back for weeks or months, for the tractor is dead. And this is easy and efficient. So easy that the wonder goes out of work, so efficient that the wonder goes out of land and the working of it, and with the wonder the deep understanding and the relation. And in the tractor man there grows the contempt that comes only to a stranger who has little understanding and no relation. For nitrates are not the land, nor phosphates; and the length of fibre in the cotton is not the land. Carbon is not a man, nor salt nor water nor calcium. He is all these, but he is much more, much more; and the land is so much more than its analysis. The man who is more than his chemistry, walking on the earth, turning his plow point for a stone, dropping his handles to slide over an outcropping, kneeling in the earth to eat his lunch; that man who is more than his elements knows the land that is more than its analysis. But the machine man, driving a dead tractor on land he does not know and love, understands only chemistry; and he is contemptuous of the land and of himself. When the corrugated iron doors are shut, he goes home, and his home is not the land.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, Chapter 11.

What strikes me most about this is how well it stands up nearly 100 years later. It still speaks of such truth. Importantly, in writing these words Steinbeck has a luxury not afforded to us today, in that he lived through this change, he witnessed the change of the guard and the human destruction wrought: he can write these words without the accusation of being a nostalgic romantic.

In this essay, I want to spell out what I understand to be the logic of Steinbeck’s machine man. This is not an exercise of that romantic nostalgia: I’m not writing this to make the case that life was better before tractors. Instead, I want to use this logic to answer a different question: why is our farmed landscape so hostile to the rest of life? Why are farms so dead?

Ultimately, however, talk of the logic of systems can only go so far. I say this mostly as a note to myself. At the end of every node in this vast global network is a person. A person who makes human decisions, neither totally free from nor subservient to this system. So this is my attempt at sketching the impersonal personal logic of agricultural economics, from the perspective of a dissident.

"Sure, nice to look at, but you can't have none of it. They's a grove of yella oranges—an' a guy with a gun that got the right to kill you if you touch one. They's a fella, newspaper fella near the coast, got a million acres—"

Casy looked up quickly, "Million acres? What in the worl' can he do with a million acres?"

"I dunno. He jus' got it. Runs a few cattle. Got guards ever'place to keep folks out. Rides aroun' in a bullet-proof car. I seen pitchers of him. Fat, sof' fella with little mean eyes an' a mouth like an ass-hole. Scairt he's gonna die. Got a million acres an' scairt of dyin'."

Casy demanded, "What in hell can he do with a million acres? What's he want a million acres for?"

The man took his whitening, puckering hands out of the water and spread them, and he tightened his lower lip and bent his head down to one shoulder. "I dunno," he said. "Guess he's crazy. Mus' be crazy. Seen a pitcher of him. He looks crazy. Crazy an' mean."

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, Chapter 18.

My dad is a commodity producer. Like most of his peers. He grows cereals for sale on the global market. In practice, what this means is that he sells to any number of grain merchants, whichever can offer the best price at the time; these merchants buy from multiple farms, normally regionally, but their reach can be national. On agreeing a price, these grain merchants will arrive to the farm with an empty artic lorry, and leave full within the hour. That is the last time that my dad will see his grain.

Already, it’s worth noting the absurdity of this relationship. Dad, like so many of his peers, will never eat what he has grown. That is utterly whack. A few years ago, after one good harvest, I remember dad proudly exclaiming “you can nearly eat this stuff!” My dad could be mining the earth for gravel, or processing scrap metal, and the relationship would be the same. This is the reductionism of Steinbeck’s machine man.

But we’ll continue. From the farm, these artic lorries drive to centralised storage hubs. By collecting grain into a small number of massive distribution centres, these grain merchants can command a better price. This is known as a grain pool. From the there, the grain is sold to a distributor, or at least works with one, to move this grain to wherever is willing to pay the best price. Most often, in my dad’s case, this is continental Europe, or occasionally North Africa. After due negotiations, the grain arrives at a shipping port; there, it is packaged and shipped, via a fleet of lorries, cranes, and boats. Sent on its way.

My dad knew someone who knew someone (plus or minus a few in the chain) who lost his whole farm by selling through these grain pools. He tried to blend a bit of excess seed-wheat with the wheat he has agreed to sell. He hoped that this would go unnoticed. The proportion of seed wheat of the total volume of his own wheat was tiny, let alone the volume of the massive grain pool. Seed wheat is normally coated, or dressed, with a host of toxic chemicals. These chemicals favour the plant’s establishment — mostly by simply being toxic to the various hungry creatures that may live in the soil. By the time that anyone realised that he had snuck in this extra seed, it was sitting in a vast storage vat of half-a-million tonnes. The toxicity was deemed to have spread, rendering the entire load not fit for the human supply chain. And so the new owners of this grain were forced to discard millions of dollars of grain. After legal action, the farmer responsible for the contamination was forced to pay, and so forced to sell his entire farm to pay the debts. But I digress.

When the grain arrives into the various ports of the world, the process repeats itself in reverse. Through various hands of distributors and processors, each adding their own layer of obfuscation, the grain will eventually become livestock feed. This is primarily for large feed-lot styled farms, where the diet of the animal is primarily bought-in feed, because these farms operate at a scale necessary for the distributors to make money. From there, the grain itself is no more, but the process starts again, through the slaughter and sale of livestock. Another set of distributors, abattoirs, and processors interfere in ways variously useful or otherwise, before the remnants of animal carcass reaches supermarket shelves, often shelves back here in the UK. There, they are consumed in total ignorance and anonymity, with an impossibly complex chain obscuring any notion of provenance beyond comprehensibility.

As a small testament to the many hands involved in this process, the price for milling wheat floats somewhere near £200 per tonne. Bread flour, in a supermarket, floats somewhere near £2 per kilo, or the equivalent of £2000 per tonne. There is, approximately, a tenfold increase in price by the time it reaches the final consumer, all largely explained the number of hands in the middle. For every £1 spent in this example, 10 pennies is received by the farmer.

Arguments in favour of this system are numerous. The most common of arguments begins something like this: since the green revolution, global agriculture has become exponentially more efficient. Across the board, yields have increased, largely thanks to the focused application of scientific understanding the problem of crop production. We feed more people now than ever before, and any suggestion that this system should be changed is akin to wanting billions of actually living people to starve to death. Regrettably, these efficiency gains might have come at the expense of the global biodiversity that once found a home on our farms. However, people need feeding, and so we must continue. We cannot forgo this newfound efficiency, and there is no going back.

Now, there’s some truth to this argument, certainly. And I don’t want to split hairs, or get lost in the minutes of inter-governmental reports: it’s boring to write, and even more boring to read. But I do want to suggest that the use of the word efficiency is at best misleading, and at worst lazy. Rather, I would suggest, since the green revolution, we have increased efficiency of production at the expense of efficiency of distribution. We now produce vastly more per hectare than ever before, but in order to get this food to its final destination, we have created a sprawling system of distribution infinitely less efficient than what it replaced. (To give one example, both amazing and absurd, in this news article from a few years ago, cod caught in the North Atlantic was to be sent to China, filleted, and then sent back to UK supermarkets.) Furthermore, exponential increases in food production have been matched by exponential increases in food waste, because the new system of distribution necessarily has its inefficiencies. By some estimates, up to a third of all food grown globally is wasted. And, as I noted in a previous essay, nearly 40% of UK grown crops are fed to livestock — an exercise in inefficiency so obvious that only so-called experts could think otherwise. The problem of “feeding the world” is currently one of distribution, not production.

The deliberate act of equating efficiency of production to efficiency in general is precisely the mindset of Steinbeck’s machine man. Overwhelmed by the level of complexity in the sprawling global food system, the analyst returns to her scientific training. Science, scythe, and schism all have the same etymological root: skei-, Proto-Indo-European root, meaning "to cut, split". And so the analysis proceeds by breaking things down, splitting things apart, reducing their complexity, and simplifying. By breaking the global food system into discrete chunks — one called distribution, one called production, one called retail, another called processing — the question of whether agriculture has become more efficient can be answered simply, and in the affirmative, free from the difficult questions that may well be posed by the various self-interactions and feedback-loops of this holistic system. Yes, agriculture is more efficient, because we now grow more food per hectare. Phew, that was quite simple in the end.

Crops were reckoned in dollars, and land was valued by principal plus interest, and crops were bought and sold before they were planted. Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops, little manufacturers who must sell before they can make. Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not also a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them.

And all the time the farms grew larger and the owners fewer. And there were pitifully few farmers on the land any more. And the imported serfs were beaten and frightened and starved until some went home again, and some grew fierce and were killed or driven from the country. And the farms grew larger and the owners fewer.

And it came about that owners no longer worked on their farms. They farmed on paper; and they forgot the land, the smell, the feel of it, and remembered only that they owned it, remembered only what they gained and lost by it.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, Chapter 19.

Industrial agriculture is a highly specialised affair. Entire farms, thousands of acres, are devoted to the production of a small handful of crops. As a conventional arable farmer, my dad grows at most four different plants in one year: wheat, barley, oil seed rape, and beans. It is not unheard of for some farmers to produce even less diversity than this: dedicated pig farmers, or entire orchards devoted to a single variety of apple.

The history of specialisation on farms is variously complex and multi-faceted. And so, a good place to start with the oversimplification of this history is with the Haber-Bosch process. It is the process used to create synthetic ammonia, otherwise known as Nitrogen fertiliser. It was discovered in 1913, and for his work Fritz Haber was awarded the 1918 Nobel Peace Prize in Chemistry. Fertility could now be bought from a factory. This was a big deal.

Historically, fertility was managed through the use of grazing livestock. The golden hoof. To give one example from medieval farming practices: livestock would graze common land during the day, and were brought into grain producing land overnight. This was known as “folding”. Livestock eat the grass of marginal land, digest, and depose of these nutrients in the form of shit where needed most: a highly efficient method of moving nutrients to grain producing land. There are levels of detail that I’m omitting, mostly because it would quickly descend into nit-picking technicalities, but the key take-away message is this: the separation of farmers into “arable” and “livestock” farmers is a uniquely modern phenomenon, made possible only through synthetic fertiliser, itself only made possible through cheap oil. Previously, these two systems were inextricably interlinked, dependent upon the other to function. All farmers were “mixed” farmers.

In the advent of the Haber-Bosch process, this ceased to be necessary. Farmers were now free of the need to integrate livestock. The golden hoof was now available for purchase.

Initially, some claimed that synthetic fertilisers would eliminate the need for crop rotations entirely. This was a bold claim. Rotating crops prevents disease build-up, confuses pests, and supports different families of soil microbes; it also facilitate the integration of livestock, in an ecological restorative manner. Farmers couldn’t have been mixed farmers without crop rotation. In the absence of artificial fertilisers, fields would have been rested after a wheat crop or two, and during this rest period was grazed by livestock. This system, plus or minus a few details, is the textbook approach of modern organic arable farmers today.

Early agricultural research centres, such as the still extant Rothamsted Research centre, tried to prove this claim in some of their earliest experiments. To quote John Letts: “By the late 19th century, agricultural scientists were claiming that there was no need to rely on natural processes or leguminous crop rotations to keep soil fertile, because yields could be maintained indefinitely with artificial fertilisers… With the arrival of artificial fertilisers, many farmers abandoned crop rotation entirely, but yield eventually began to stagnate due to acidification, fertiliser “burn”, soil compaction, and a massive decline in soil organic matter. Wheat yields dropped 40 percent in Germany in the 1920s, and overuse of soils in the USA reduced yields and resulted in the dustbowl in the central plains in the 1930s.” From one John to another. For nitrates are not the land, nor phosphates; and the length of fibre in the cotton is not the land. Carbon is not a man, nor salt nor water nor calcium. He is all these, but he is much more, much more; and the land is so much more than its analysis.

In light of such failures, it became clear that chemical fertilisers could not replace the need for crop rotations. However, it could replace the need for integrated livestock. This is where we find ourselves today, with specialised arable versus livestock farmers. The point that I want to make is that it’s a technological jump that has facilitated degrees of specialisation previously unthinkable.

But this is nothing if not the history of industrialisation. Technological improvements to facilitate efficiency grains through specialisation. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. And with specialisation comes its allies, consolidation and accumulation. The logic of industrialisation was set in motion by artificial fertilisers, but it certainly didn’t stop there.

Over the years, farms have become more and more specialised. Diverse orchards erased in favour of a single variety of apple. Old-school mixed farms reduce in complexity. Even at the level of the field, diverse populations of grain replaced by a single cultivar, a monoculture. With this specialisation, comes the need for specialised equipment, and so the need for generalist labour disappears. When my grandfather first arrived to the farm, there was about 20 members of staff, a few acres of orchards, livestock, cereal, even a field of cabbages. His first managerial decision was to fire all staff, tear up the orchard, plough over the cabbages, sell the livestock, and commit to wheat. He speaks with pride of this grand act of simplification. The logic of the time was to get big, or fall behind.

Invariable, the equipment necessary for this specialisation is dear, saying nothing of the cost of land itself. My dad has one machine dedicated exclusively for planting one plant, beans, which is worth well over £30k new. This makes it incredibly difficult for new entrants to join farming. And so it becomes very difficult for old farmers to leave farming, without familial succession. In a back-of-the-envelope calculation, at today’s prices, it would take over 100 years for the initial investment on an arable farm to pay itself back. 100 years! 4 generations! It is hardly surprising that the average age of farmers in the UK is 59. No one can afford to buy them out, and their children have long since left the farm to earn a proper salary in the city.

But the most interesting consequence of this specialisation is the types of markets that emerge. The people in my local town of Paddock Wood can’t exist on an exclusive diet of wheat, barley, oil seed rape, and beans — no matter how hard they may try. The cabbages are gone, and the orchards have signed exclusivity rights to Tesco’s. And so my dad must sell elsewhere. Each region of England has its specialty, each region of the industrialised world, and each must export to import.

In the search of efficiency of production, the logic of specialisation means that each region has a huge surplus in a tiny number of crops. In order to facilitate the global redistribution of this specialisation, vast networks of distribution must be created. Unthinkably, unfathomably vast and complex, all made possible by cheap oil. Global markets are born in response to this problem of distribution, and so efficiency of distribution is lost. In the search of efficiency of production, the idea of any local or regional autonomy is totally forsaken.

And from within this system of scale, the only option for its producers is to further its logic. My dad can’t (re)create a new, fairer, system of distribution by himself, not after such specialisation. His only market is the global market. And so his best and only hand is to increase yield, so that he has more to sell, thus scale furthers the need for scale. The insidious logic of this system is that once it starts, it gathers its own momentum. Efficiency of production can be improved upon at the level of the individual — whether that’s a single field, a single farm, or a single company. But efficiency of distribution is no singular individual’s business: it materialises (or dematerialises) from the collective, intentionally or otherwise.

In the search of efficiency of production, efficiency of distribution is necessarily abandoned. We cannot have both.

The great highways streamed with moving people. There in the Middle—and Southwest had lived a simple agrarian folk who had not changed with industry, who had not farmed with machines or known the power and danger of machines in private hands. They had not grown up in the paradoxes of industry. Their senses were still sharp to the ridiculousness of the industrial life.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, Chapter 21

The system does not and cannot exist to satisfy human needs. Instead, it is human behaviour that has to be modified to fit the needs of the system.

Theodore Kaczynski, Industrial Society and its Future

Allow me to try to be explicit in sketching the logic of this agricultural system. It is the logic that dominates our landscapes today. It is this logic that explains so much of why our farmlands are so dead. It also the logic that explains why the system that utterly depends on farmers can nevertheless be so exploitative of farmers.

As far as I can understand, the logic starts with efficiency of production. This, in and of itself, is fairly benign, and also older than industrialised agriculture. Who doesn’t want a bountiful harvest? More grain is more bread and more beer, both of which is a good time. The uniquely industrial flavour is to be scientific in the literal sense, and to scythe apart. As I have hinted a few times already, previous systems of agriculture were also very efficient, if one takes this to mean resourceful, frugal, not wasteful. There was a holistic efficiency not readily intuitive to a scientific mindset. By cutting things apart, what now matters most is the amount produced for market by a single entity — whether that’s a cow, a field, or a farm — regardless of what it cost to get there. This holistic efficiency was able to lie hidden because it often operated outside of market economics. To give an example, it was common for schools and hospitals in Victorian England to feed all kitchen waste to a small unit of pigs kept in the back garden; these animals would be slaughtered nearby, and fed back to the students and patients. Incredibly efficient, all with the least economic impression.

Wheat yields in the UK have increased four-fold in the last 100 years, but this is only possible with an equally grand increase in inputs — fertilisers, herbicides, fungicides, etc. The modern arsenal of agrochemicals. Importantly, this arsenal is entirely oil-derived; the only reason that is has been possible to be single-mindedly focused on yield, heedless of what it takes to get there, is because oil has been cheap.

In order to achieve this huge increase in yield, it has been necessary to specialise. With specialisation comes consolidation. Huge surpluses that far exceed local demand can only be processed by buyer of immense size, and so the massive networks of global markets are born. Slowly at first, eventually these come to dominate, and finally we arrive where we find ourselves today: the global commodity market and supermarkets are effectively the only market for most farmers.

In the singular focus on yield, quality is degraded. We all know this intuitively. Dead bread of Hovis’ tasteless sliced white. The race to the bottom has begun. Distributors and processors gave become so large that they now set the terms; these terms are not guided by human health, but by efficiency of production and processing. Uniformity becomes the benchmark, and so death to diversity, both in the fields and on the supermarket shelves. What was originally conceived of as an engine oil becomes the third most widely consumed cooking oil in the world — “vegetable oil” or oil seed rape — because it fits well as a break crop in an arable rotation, and because it can be harvested with the same machine as wheat.

The only route under this logic is scale, because scale brings yield. Farms get bigger, machines get bigger, farmers become fewer. Diverse patchwork landscapes become simplified. Under scale and specialisation is born the monoculture, unheard of in nature, ecological disasters. Farmers must fight harder and harder to assert their will. Insects only eat sick plants, and so insecticide must be developed to mask the sickness. Nature abhors a vacuum, and so herbicide is needed to kill the weeds. In the absence of integrated livestock, natural fertility declines, and so chemical fertility is needed to fill this void. The whole process still lubricated by the flow of cheap oil.

And now this logic is ready to be exported, a truly global market. And the global market is the promise of California. The promise of scale, of yield, of uniformity, of growth, of the future. The promise to each farmer of a better life. And like the promise of California, the promise is broken.

The world is now one big competition, and it is farmers who must fight farmers. The orchestrators and beneficiaries of such a fight, the traders in London, New York, Tokyo, they don’t care if your harvest fails. Rain or shine, they’re there to make money, and money can be made either way. The tiny fields of rural Devon fight against the million acre ranches in Australia.

Survival of the fittest brings the betterment of us all. Grow up, get big, or get out.

But what happens when there are no farmers left to fight? What happens when they’ve all got out?

Men who can graft the trees and make the seed fertile and big can find no way to let the hungry people eat their produce. Men who have created new fruits in the world cannot create a system whereby their fruits may be eaten. And the failure hangs over the State like a great sorrow.

The works of the roots of the vines, of the trees, must be destroyed to keep up the price, and this is the saddest, bitterest thing of all. Carloads of oranges dumped on the ground. The people came for miles to take the fruit, but this could not be. How would they buy oranges at twenty cents a dozen if they could drive out and pick them up? And men with hoses squirt kerosene on the oranges, and they are angry at the crime, angry at the people who have come to take the fruit. A million people hungry, needing the fruit—and kerosene sprayed over the golden mountains.

And the smell of rot fills the country.

Burn coffee for fuel in the ships. Burn corn to keep warm, it makes a hot fire. Dump potatoes in the rivers and place guards along the banks to keep the hungry people from fishing them out. Slaughter the pigs and bury them, and let the putrescence drip down into the earth.

There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolise. There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange. And coroners must fill in the certificate—died of malnutrition—because the food must rot, must be forced to rot.

The people come with nets to fish for potatoes in the river, and the guards hold them back; they come in rattling cars to get the dumped oranges, but the kerosene is sprayed. And they stand still and watch the potatoes float by, listen to the screaming pigs being killed in a ditch and covered with quick-lime, watch the mountains of oranges slop down to a putrefying ooze; and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, Chapter 25.

So far, I’ve done what I promised to try to avoid: I’ve written about impersonal logics of an impersonal system, its past and future inevitable simply because possible. But, whilst true to a large extent, I don’t believe this to be the full story. This is what people like Kaczynski get wrong, and what led him to sending pipe bombs in the mail. At the end of every node in this grand sprawling system, there are people. People who make human decisions.

The logics of scale are sexy and alluring. They offer real benefits. It is not a surprise that they dominate. The closest apple orchard to the farm sells exclusively to Tesco’s. The farmer has very little control of the price, but every single apple that my neighbour grows has a guaranteed market. This is the advantage, at least ostensibly, of scale. Yet, if this advantage truly benefited the farmer, if the promise of scale really worked, then Tesco’s would be buying farms. But they’re not. Someone said exactly this to me earlier in the year, and it hit me as a moment of clarity. Tesco’s are happy to be your grocer, your bank, even your mobile network, but they draw the line before becoming your farmer. It’s cheaper to let farmers make a loss than it is to farm it themselves. It is the farmers who are being farmed.

And so the solution, such as it is, is to move away from the logic of scale, and all its sexy convenience. Or rather, I should say, my solution, and not the solution. This is the mentality of scale and global markets: what works in one place works everywhere, because there is no difference, a single solution ready for export. The best that I can offer is what (I hope!) will work here. Maximising yield is exceptionally resource heavy. This has a huge cost, financial and ecological. It is the race to the bottom, in the most literal sense: the only objective is scale, but these super-yielding varieties are so degraded in quality that they seldom meet the requirements for human consumption. That, at least, has been the case at home.

Instead, I want to grow without the arsenal of agrochemicals. I want to grow varieties that work in such a system. I want to grow for people. I want to make real bread with my wheat, and not fatten someone else’s cow. But to do this, I can’t sell to a commodity market, the anonymous global market. I need to find people who share my vision, and who are willing to pay for it. This is not a new idea, and, thank God, this is not a one man fight against the world. This is the work of the UK Grain Lab, who have done so much to facilitate the legal work behind the exchange of heritage grains. This is work of the Heritage Grain Trust. This is the Real Bread Campaign. This is people focused agriculture.

Throughout this essay, I’ve been arguing that the dominant agricultural system boasts a particular type of efficiency: an efficiency that wastes up to a third of food globally, feeds 40% of UK grown crops to livestock, loses approximately 3 million tonnes of UK topsoil each year, amongst other highly efficient practices. We are able to call this a more efficient system than what it replaced, I have argued, because the focus has been placed exclusively on efficiency of production, at the expense of efficiency of distribution. But, like with all categories, these two idealised poles aren’t perfect. And more importantly, the language obscures why any of this matters. Who cares about an academic distinction between types of efficiency anyway?

So let me propose two replacement terms: scale focused agriculture, and people focused agriculture. To build a people focused agriculture, one must have efficiency of distribution. To know your farmer, you must have efficiency of distribution. In the words of Wendell Berry, people focused agriculture allows one “to become acquainted with the beautiful energy cycle that revolves from soil to seed to flower to fruit to food to offal to decay, and around again”. Inhumane factory farms, pigs that never see the light of day or never have dirt underfoot, are the consequences of scale focused agriculture. Vast acres, entirely closed to the public, and dead of all life except one plant, are the consequences of scale focused agriculture. To build a people focused agriculture, one must move away from scale and yield as the only metric of success. At the end of every node, there is a human decision to be made, and it is at this level that one can choose otherwise.

But this is a lot of talk. I’ve been writing this essay for far too long. Talk of a new agricultural system is cheap and easy. Much harder to do. That’s where the real work is. Finding these people, working with these people, growing this grain. Building a home in Oklahoma, rather than exhausting in the promise of California. People focused agriculture, all in the name of real bread.