I saw a man,

An old Cilician, who occupied

An acre or two of land that no one wanted,

A patch not worth the ploughing, unrewarding

For flocks, unfit for vineyards; he however

By planting here and there among the scrub

Cabbages or white lilies and verbena

And flimsy poppies, fancied himself a king

In wealth, and coming home late in the evening

Loaded his board with unbought delicaciesVirgil. The Georgics: Book IV

The new Labour Government recently announced a 20% inheritance tax on all farm assets over £1million. This, ostensibly, was implemented to “close the loophole” that allowed wealthy land-owners to avoid paying inheritance tax on farm assets. The assets under question are not limited to the land itself, but includes any equipment and buildings necessary for the farm to function. Before this announcement, farm wealth could be passed from one generation with almost total impunity.

Superficially, Labour are correct, in that such a loophole does exist: land was and is being bought because of the favourable inheritance tax rates. To quote Strutt and Parker:

Non-farmers bought more than half of the farms and estates sold on the open market in England in 2023, with farmers accounting for the lowest level of transactions on record. Analysis shows that farmers accounted for only 44% of open market transactions in 2023 when historically they have tended to be involved in 50-60% of purchases.

Meanwhile, non-farmer buyers – who are a mix of private and institutional investors and lifestyle buyers – accounted for 56% of sales, and because they also tend to buy larger farms, they bought a larger area of land than farmers too. Private investors were involved in 28% of transactions, institutional investors in 13% – a rise of 10% on 2022 levels – and lifestyle buyers in 16%.

Part of what makes land such a good investment is its impunity to inheritance tax. This is true.

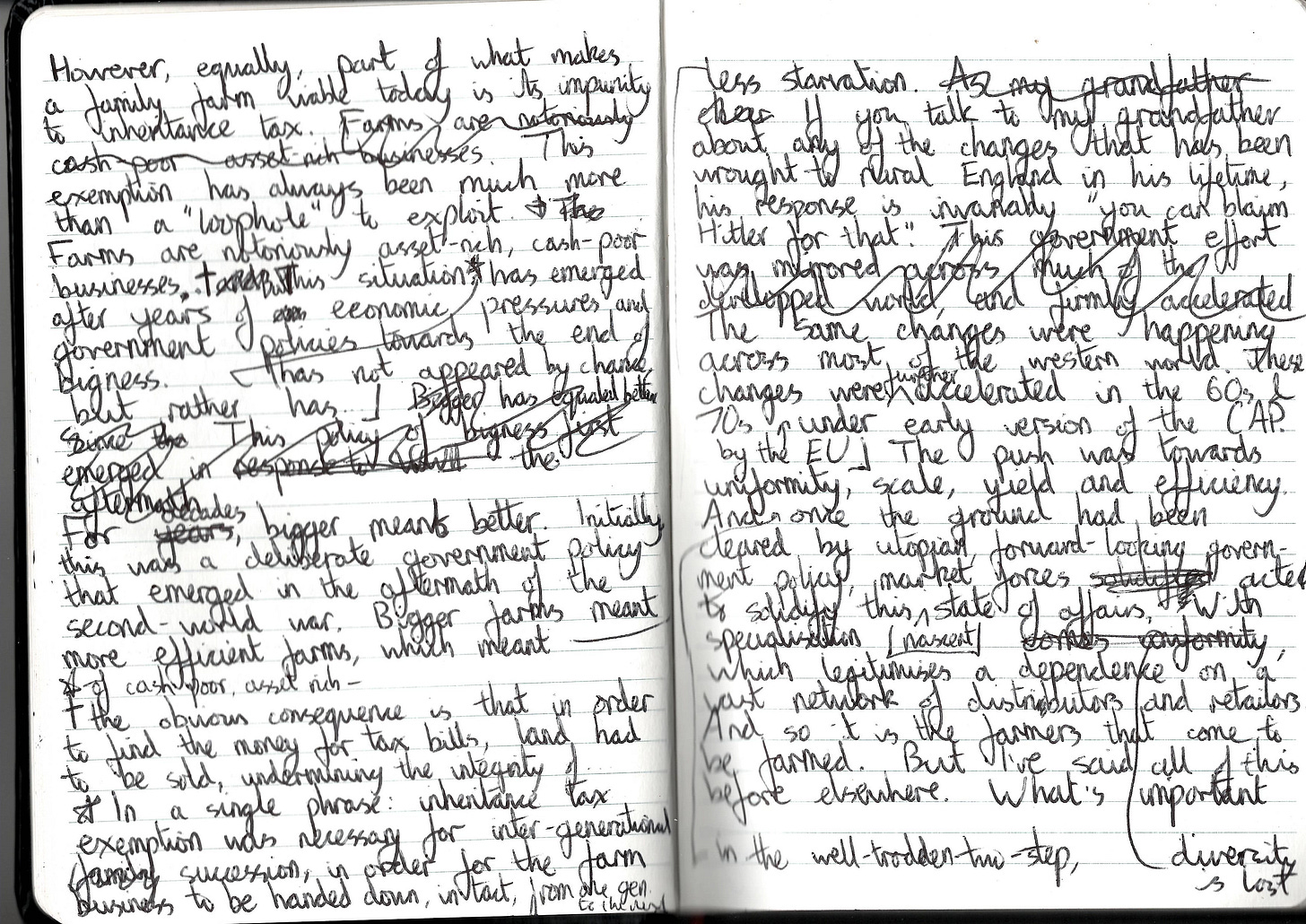

Equally, however, part of what makes a family farm viable today is its impunity to inheritance tax. This exemption has always been much more than a “loophole” to exploit. Said simply: the inheritance tax exemption is necessary in order for the farm to be handed down, intact, from one generation to the next. The cliché is that farms are notoriously asset-rich, but cash-poor. The obvious consequence is that, without tax exemption, land had to be sold to pay tax. This was a large part of why the total exemption was first introduced in the early 1990s: to maintain the integrity of family farms.

This situation, of asset-rich cash-poor farmers, has not always existed, and has not appeared by chance. Rather, it has emerged after years of government policies, deliberately directed towards the end of Bigness. For decades, bigger meant better. Initially, this was a position that emerged in the aftermath of the second world war. Bigger farms meant more efficient farms, which meant less starvation. If you talk to my grandfather about any of the changes wrought upon rural England in his lifetime, his response is invariably “you can blame Hitler for that”. These changes were not limited to England: the governments of much of the western world adopted a similar strategy. In the words of the 1970s U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, "Before we go back to organic agriculture, somebody is going to have to decide what 50 million people we are going to let starve.” The push was towards uniformity, scale, yield, and efficiency. And, in the well-walked two-step, once the ground has been cleared by utopian, forward-looking government policy, it is strip-mined by market forces. With specialisation diversity is lost, which necessitates a dependence on a vast network of distributors, processors, and retailors. Hence, the “global market” becomes viable. And so, it is the farmers that come to be farmed. But I’ve said all of this before elsewhere.

What’s important for this essay is that as farms became bigger and more specialised, they became more dependent upon both government subsidies, and agribusiness. This, in turn, forces farmers further into a system that is necessarily exploitative of both people and the land that sustains them.

As with most things that I try to say, it’s already been said before, more eloquently, somewhere in the writings of Wendell Berry. This case is no exception:

In agriculture, the economy of scale or growth directly destroys land, people, neighbourhoods, and communities. And so good agriculture is virtually synonymous with small-scale agriculture – that is, with what is conventionally called "the small farm." The meaning of "small" will vary, of course, from place to place and from farmer to farmer. What I mean by it has much to do with propriety of size and scale. The small farm is defended here because smallness tends to be a prerequisite of diversity, and diversity, in turn, a prerequisite of thrift and care in the use of the world. In general, I believe, small farms tend to be diverse in economy, which is to say complex in structure; whereas the larger the farm, the more likely it is to specialize in one or two crops, to have no animals, and to depend on chemicals, purchased supplies, and credit. In agriculture, as in nature and culture, the more complex the system or structure (within the obvious biological and human limits), the more sound and durable it is likely to be. The present industrial system of agriculture is failing because it is too simple to provide even rudimentary methods of soil conservation, or to be capable of the restraints necessary for the survival of rural neighbourhoods, and because it fosters a mentality too simple to notice these deficiencies.1

All of this brings me nicely to the current issue of inheritance tax. Farms have not come to be the size they are by chance. It is years of government policy, and years of “global markets”, that has made farmers so asset-rich but cash-poor, and thus so vulnerable to this new legislation. That goes some way to explaining why farmers are so enraged by this proposal: bigger has always been better, until it suddenly isn’t. Yet my talk of government policy and market forces, and the tone of the public debate, clouds what feels like the heart of this issue. The question lying beneath it all is this: is land primarily real estate? Is land simply an asset to accumulate? Relatedly, in the words of Tolstoy: how much land does a man need? How big should a farm be?

The language of the public conversation obfuscates the deeper, and more ancient relationship to land. To speak generally, this more ancient relationship says that we’re not really owners of land. It says that we never really can “own” land, because it’s not ours to own. It says that we should be custodians of the land, and that good work, and by extension healthy culture, is centred about the proper care of land. This is most obviously revealed in the language we use: agriculture and care have the same etymological root. Both words derive from the Latin cultura, which, more literally, means “to cultivate”, as in “the tilling of land”. More figuratively, cultura can be understood to mean “an honouring”. In order for there to be custodianship, there must exist a culture, and by extension an agri-culture, that allows for the specificities of this knowledge to pass from one generation to the next. This is the sense in which, properly understood, land can be inherited: an inheritance of the obligation of care towards one’s home.

If that feels vague or bucolic, or even just abstract, then I would argue that this is because our culture, and its relationship to the land that sustains it, has moved so far from this deeper, more ancient view. This, in no small part, can be explained by decades of Bigness. Today, land is primarily viewed as an asset class, unmoored from these restrictive, backwards obligations. And when land is simply another asset class amongst many, the question rightly emerges: why should it be exempt from taxation?

I don’t want to be misunderstood: the ability to buy and sell land is not evil. There are legitimate reasons for people both to buy and sell land, to move on from one place or to move into another. I’m not saying that the only legitimate form of land ownership is ancestral bequeathment, outside of law, in some vague gesture of “indigeneity”. As a farming friend said, a farm shouldn’t be a prison sentence. And it follows that in order to facilitate this buying and selling, there must be a reductive legal apparatus in place. Reductive in that it reduces the totality of land, with all of its obligations, to a tradable asset. What I am saying is this: the legal apparatus is secondary to the primary fact of custodianship. It emerges only after the underlying reality of the need to care for land. We have been landed people for far longer than we have been legal people.

Again, to quote Wendell Berry:

If we read the bible, we will discover that we humans do not own the world or any part of it: “The earth is the Lord’s, and the fulness thereof: the world and they that dwell therein.” There is in our human law, undeniably, the concept and right of “land ownership”. But this, I think, is merely an expedient to safeguard the mutual belonging of people and places without which there can be no lasting and conserving human communities. This right of human ownership is limited by mortality and by natural constraints on human attention and responsibility; it quickly becomes abusive when used to justify large accumulations of “real estate”, and perhaps for that reason such large accumulations are forbidden in the twenty-fifth chapter of Leviticus. In biblical terms, the “landowner” is the guest and steward of God: “The land is mine; for ye are strangers and sojourners with me.”2

This ancient view, as I have been calling it, is fundamentally a Christian view. It is also the view held by most, if not all, indigenous cultures. As explained by Robin Wall Kimmerer:

The currency of a gift economy is, at its root, reciprocity. In Western thinking, private land is understood to be a “bundle of rights,” whereas in a gift economy property has a “bundle of responsibilities” attached.3

We cannot, in any true sense, “own” land because it is not ours to own. And so, our correct position is one of custodians, and all of the complex demands that that makes of us. In the absence of a God, or the absence of a gift economy, then land simply becomes one asset class amongst many. It becomes “real estate” to be accumulated. And so, the lack of inheritance tax becomes a “loophole” for corporate investors to exploit.

And so, in principle at least, I agree with what Labour has claimed that they are trying to do. Vast swaths of land have been accumulated, and inheritance tax relief has played no small part. Furthermore, land-as-real-estate obfuscates this more ancient relationship to land – a relationship common both to our Christian history, and to indigenous landed cultures. Land-as-real-estate also makes writing like this feel painfully romantic or nostalgic, or simply naïve to the so-called realities of the world. Thus, I believe that careful efforts to break up large accumulations of real estate is good. The devil is, as they say, in the detail.

As I mentioned above, Labour have “closed” the loophole by instating inheritance tax on all farm assets above £1million. Nominally, this sounds like a lot of money, and in a sense it is. Labour have promised vaguely that “most” working farms will be unaffected, and that only the largest estates will pay this tax.

In an attempt to investigate this claim, some ball-park figures may be useful. In what follows, I speak only of arable farms because that is closest to what I know.

Arable land, on average, is near £10,000 per acre: otherwise said, 100 acres is worth £1million. A combine harvester costs somewhere on the order of a £250,000 when new. A new tractor, near £100,000. A drill, near £50,000. Then there’s a sprayer, fertiliser spreader, slug pellet applicator, whose value, for easy maths, totals somewhere near £100,000. That is the bare minimum in terms of machinery to get that crop planted and harvested. (I haven’t included any number of optional extras: inter-row hoes, flail mowers, precision weeder, etc.) That totals to around £500,000 of machinery.

According to DEFRA, the average farm in this country is 81 hectares, or just over 200 acre4. Arable farms tend to be larger than other types of farms, because of the economies of scale necessary to afford such machinery, but exactly by how much is hard to say definitively. In the east of England, where arable farming dominates, the average farm size is 123 hectares, or just over 300 acres. To be conservative, let’s say that 300 acres is broadly representative of the average arable farm size across the country. (My intuition tells me that this is too small, but I can’t justify this with any numerical certainty.) Thus, our average arable farm has a value of £3million in land alone.

Now, add in the value of machinery, and farm buildings, and the total wealth sits at somewhere near £4million – well above the £1million threshold that Labour has claimed leaves most farms unaffected.

The average net margin, i.e. the profit per hectare before rent and debts are due, for arable farms is projected to be £258/ha in 2024. Multiply that by our average farm size, and one arrives at £31,724 per year. This is a return of less than 1% per year on farm assets: farmers would be better off to sell the lot, and put it in a Lloyd’s easy-saver.

This oversimplified calculation should demonstrate two things:

1. Almost every arable farm will exceed the threshold value. Every time that you eat British-grown oats, wheat, beans, barely, peas, vegetable oil, etc., it has come from a farm whose total value exceeds the threshold. And so, I would politely like to dispute the claim that “most” farms will be unaffected.

2. Our simplified example farm would have a tax bill of near £600,000. With an annual profit of near £30,000, it would take 20 years to pay this tax bill. Simply put, the annual income is utterly insufficient to pay the tax bill.

The immediately obvious consequence of these two points is that land will be forced onto the market to pay the tax. And it is not the farmers who will be buying land, at least not on average. My humble prediction, and I’m not alone, is that this change will free up more land for the large estates, corporate land holdings, professional land-lords, pension funds – in a word, all of the groups that this change was ostensibly designed to disadvantage. And most crucially, land remains a good investment. Inheritance tax on nearly every other asset class is 40%, double the newly proposed rate on land. The incentive to sequester wealth in land-as-real-estate has not been eliminated. The “loophole” has not been closed.

And in an age of climate anxiety, with its associated corporate culpability and so corporate greenwashing, land-as-real-estate takes on another dimension: carbon offsetting. More land will be bought by corporations with a green marketing campaign to deliver, in a delicate game of carbon accounting: destruction over there, perfectly balanced with carbon captured over here. This is not undue cynicism, nor am I the only person making such a claim. Land is now explicitly being advertised for its value as a carbon offset. One such example:

Beyond its financial returns, UK farmland offers another compelling advantage: its carbon-negative nature. Unlike most assets that contribute to carbon emissions, such as real estate developments or manufacturing plants, farmland acts as a carbon sink, absorbing more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than it emits.

Another, from a rural estate agent:5

[The change to inheritance tax laws] will encourage more non-farmer buyers who are looking for natural capital projects which create ‘green credits’ for sale to the building and other ‘dirty’ industries.

Even if such schemes are done with the best of intentions, impeccably managed, with careful consultations with a team of experts, it will invariably mean that less people work and depend upon land directly. The inevitable fact of our interdependence with the rest of life becomes further obscured. Land, and that foreign thing called “nature”, becomes something that happens over there, out of sight, behind a thin glass veil, sequestering carbon or otherwise.

All of this is to say that the responsibility and care of land requires people who depend on land. It is only when people do not depend on land that people can abuse land – abuse with solar farms, or cheap housing, or carbon offsetting schemes, or the agrochemical poisons of scale. Any policy that forces people to sell the land they depend upon, or forces people further into an exploitative agricultural system, or encourages absentee ownership, diminishes the capacity for care. It thus furthers the view that land ownership is the collection of rights and entitlements, rather than obligations and responsibilities, because land ownership becomes an abstract fact, rather than a known truth.

All of this brings me nicely to the question that I asked earlier: How big should a farm be? How much land is enough? It’s a hard question to answer, but I do believe it worthwhile to try. And I do believe that there is an answer to find, despite the prevailing wisdom of scale. The specific answer is necessarily local and contextual, dependent upon the where and what or each farm. Yet, it seems to me, in all that I have read and all that I have witnessed, that the unifying thread to all efforts at good custodianship is that work happens at the scale of intimacy. It is when one knows land, and when one depends on land, that one can care for land. Care is not abstract. Custodianship is inherently self-limiting; it necessarily diminishes with size and scale. And when economic necessities mandate working in excess of the capacity for intimacy, abuse starts. Or, to use the simple words of Casey Joad in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath: "What in hell can he do with a million acres? What's he want a million acres for?"

At this point in the essay, my plan was to find some statistics on the size of farms, and the number of farmers, and to see how this has changed with time. I would have made the point that there are less farmers now than there have ever been, and I would have linked that to the history of scale, and the history of land abuse, which are largely the same history. But, as they say, there are three types of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics. Instead, totally by chance, this appeared to me, as if by magic, only yesterday. Dad found it whilst looking through his dad’s papers.

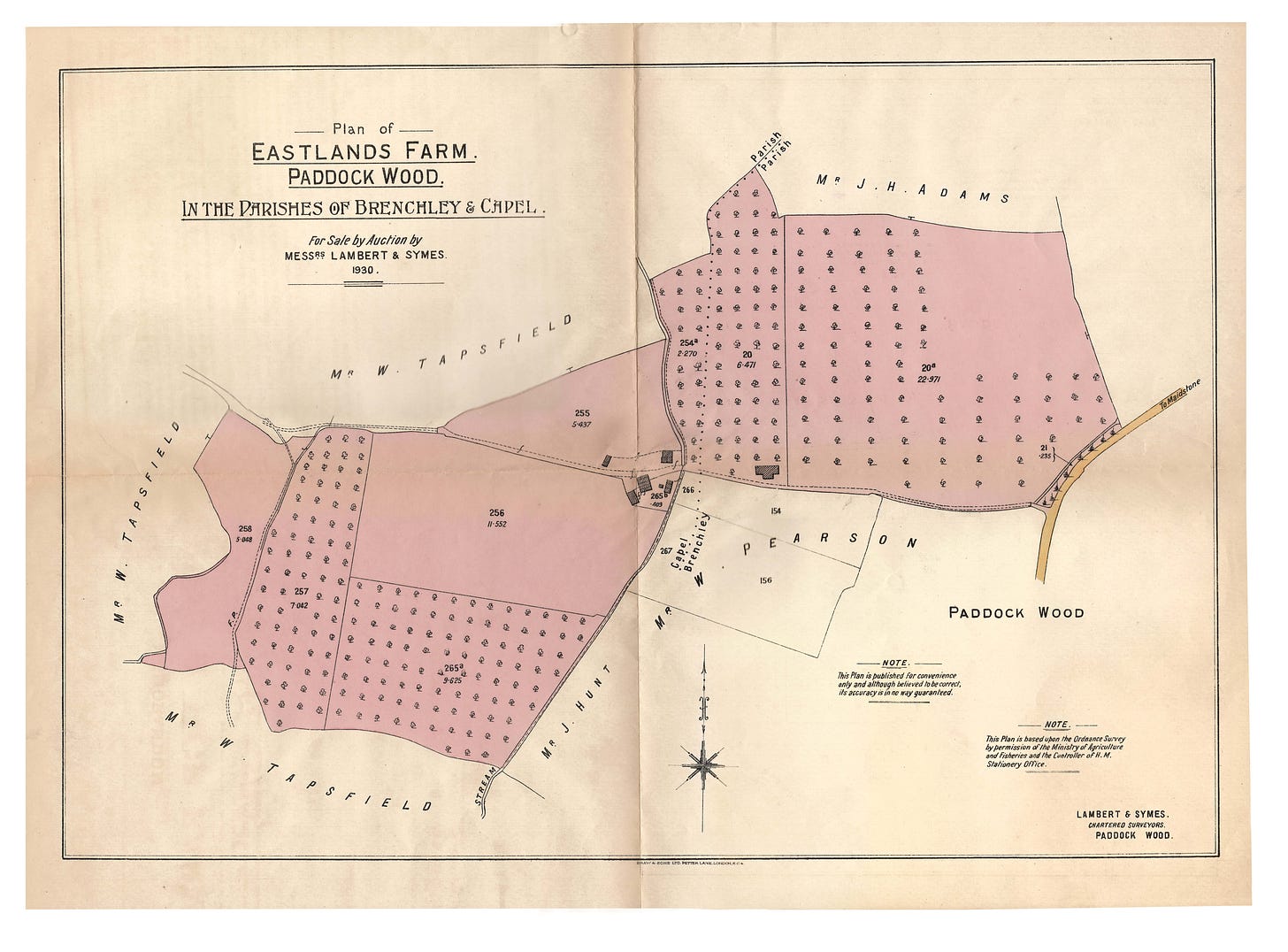

It's a map from 1930, as part of a sales brochure for “Eastlands Farm”. I ask you to look at it carefully. For sale, on the 21st of May, 1930, was “71 acres, including 42 acres Orchards and Plantations in bearing: a Pair of Cottages (1 vacant), and ample Farm Buildings. To be Sold with Possessions, the Buyer thus taking the full benefit of the ensuing Season’s Crops.” Eastlands farm is now a small part of my family’s farm, and one of those pair of cottages is where I live. What is most amazing to me is the details of the map. The names of all of the neighbouring farmers are written around its edge. Mr J. H. Adams. Mr W. Pearson. Mr J. Hunt. Mr W. Tapsfield. Each of these names were families of real people, each making a living from a small farm. None of these names remain. Entire farms, entire livelihoods, are now but a single field.

There’s forever more to say, but one must stop at some point. Perhaps, as always, it is best to let Wendell Berry conclude:6

How do we come at the value of a little land? We do so by the reference to the value of no land. Agrarians value land because somewhere back in the history of their consciousness is the memory of being landless. This memory is implicit, in Virgil’s poem, in the old farmer’s happy acceptance of “an acre or two of land that no one wanted”. If you have no land, you have nothing: no food, no shelter, no warmth, no freedom, no life. If we remember this, we know that all economics begin to lie as soon as they assign a fixed value to land. People who have been landless know that the land is invaluable; it is worth everything.

The Gift of Good Land, Wendell Berry, published in 1981. Quote taken from the introductory essay.

Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community, Wendell Berry, published in 1992. Quote taken from the essay Christianity and the Survival of Creation.

Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer, publish in 2013.

Even by their own statistics, the value of land for an average farm is double the £1million threshold, rendering their claim that “most” farms will be unaffected rather dubious. But I digress.

John Coleman, of GSC Grays, in the Farmers Guardian magazine, November 2024.

The World-Ending Fire, Wendell Berry, published in 2017. Quote taken from the essay The Agrarian Standard.

This is super interesting Leon.