A Spring Update

Where (almost) everything that could have gone wrong did go wrong. But where things largely turned out okay.

The best-laid plans of mice and men oft’ go awry. Or at least that’s how it’s felt over the last few weeks. At times, it honestly felt as though something was cursing us. Someone, somewhere did not want us to put wheat in the ground.

But we managed. As I write, and as you read, a few million grains of weird wheat have found their new home amongst 20 hectares of Kentish clay. And, breathe a sigh of relief. The only thing to do now is to pray for rain, and then the miraculous process of germination to growth to harvest to decay can begin anew.

For those who have been reading for a while, the plan that I laid out in August has changed only slightly, mostly by necessity, mostly for the best.

The original plan was to plant 20 hectares of Mariagertoba. This is a modern population of heritage grains. By that, I mean that it is the brainchild, and labour of love, of a slightly mad Danish plant breeder — Anders Borgen. Over many years, he selected individual grains from heads of wheat that he particularly liked the look of, and slowly built up a field-scale population from these grains. (It’s hard to convey just how mad this project is: building up enough seed from individual plants to be viable at field-scale is a labour of multiple years, if not decades. What’s madder is that he then gave away his life’s work, basically for free.) He was looking to create a new population of bread wheats that would be well suited for modern organic farmers: spring planting, for higher protein; taller growth habit, to outcompete weeds, without being excessively tall, to avoid the risk of falling over; diverse enough to withstand the vagaries of disease and pest threats, but not so diverse that it couldn’t make consistently good bread.

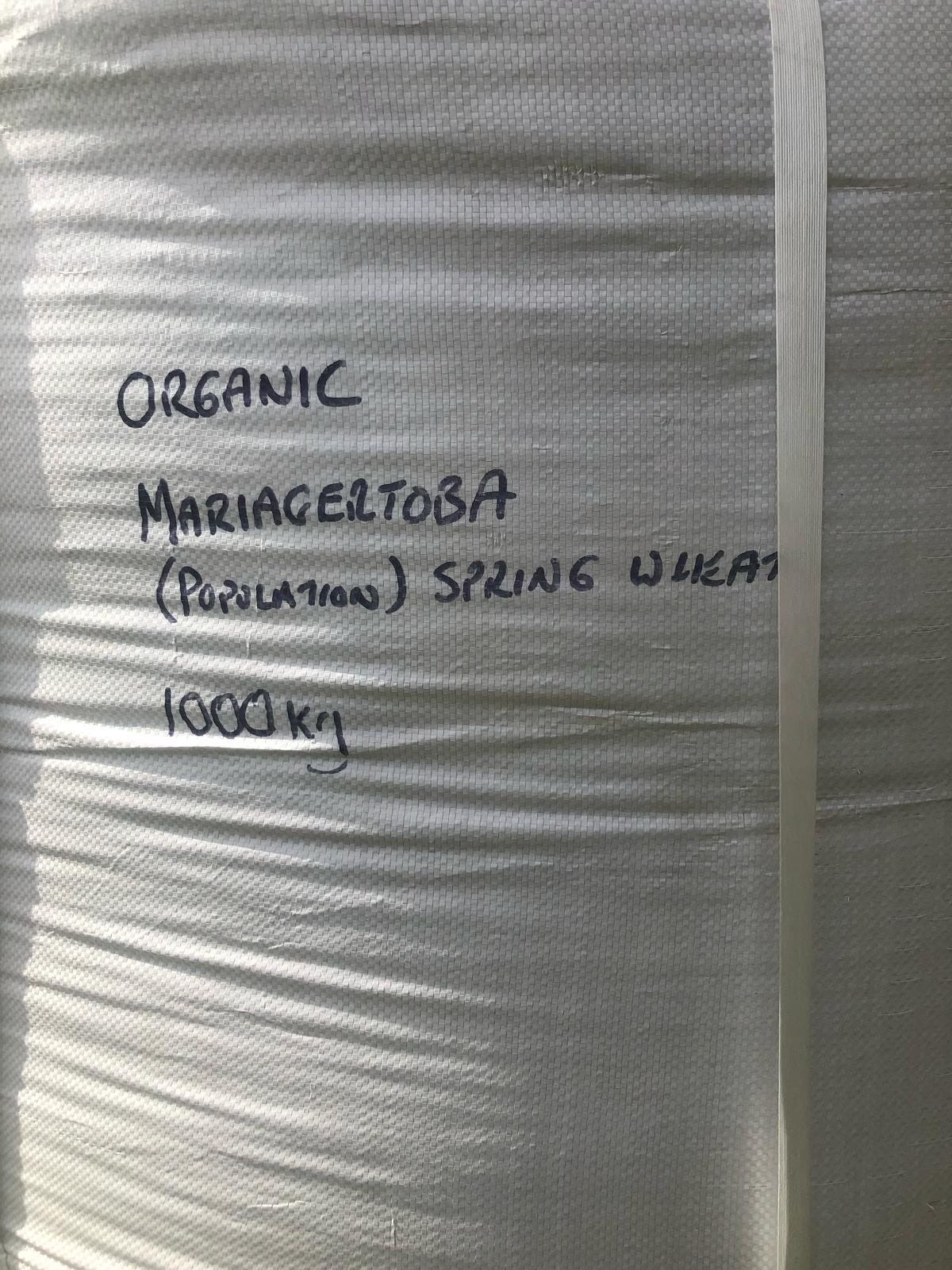

I first heard about it at Groundswell ‘24, after a conversation with someone who grew the stuff. I liked the sound of it, and was due to write an abstracted, top-down plan to present to my dad soon after. So I committed, on paper, to growing 20 hectares, and so committed to finding about 4 tonnes of seed. Alas, such abstracted, top-down plans rarely bear much fruit. 2024 was a tough year for much of arable farming in England. It was so bloody wet! This meant that there wasn’t much seed floating about. After sending what felt like a million speculative emails to anyone and everyone that I could think of, ruffling a few feathers in the process, I eventually managed to source about 1.8 tonnes of seed: good enough for about 9 hectares.

The same grower who first told me about Mariagertoba also told me about another heritage population: a landrace from Sweden, named Ölands. To borrow from Wikipedia:

A landrace is a domesticated, locally adapted, often traditional variety of a species of animal or plant that has developed over time, through adaptation to its natural and cultural environment of agriculture and pastoralism, and due to isolation from other populations of the species.

For the geographically literate amongst you, you may know that Öland is an island, off the coast of mainland Sweden. On this island, the people have been growing wheat, and saving seed, for thousands of years. Slowly, over time, the seed has adapted to the local conditions, and a landrace is born. There is nothing unique about this process per se. This is how most cereals have been grown throughout the vast majority of our species’ collective mutual history.

What makes Ölands unique is that this landrace has persisted, and its genetic diversity has endured, throughout the unfurling of industrialised agriculture. The first places to industrialise were the first to lose their localised diversity: uniformity, scale, and the reductive gaze of the scientific method was the order of the day; that which works in the lab must work everywhere. Ölands has survived precisely because it is native to the hinterlands of a remote Swedish island. It is now repopulating the mainland.

(I discovered recently that there existed a landrace of wheat adapted Wealden basin of Kent, precisely where the farm is situated, called Old Kent Red. It was the grain that fed London for nearly 200 years, and its cultivation stopped almost entirely overnight at the onset of the industrial revolution. It is now being revived, thanks to gene banks and mad plant breeders: a truly beautiful combination. I hope to grow some next year.)

I managed to find about 1.3 tonnes of Ölands, enough to plant about 5 hectares. At this point, my luck with speculative emails and strange grains was beginning to run out. I decided to call it a day, to keep my life simple, and to keep the miller happy. The remaining few hectares would be planted with Mulika: a modern organic wheat, short-stemmed, and a mono-culture. Ah pragmatism, my old adversary and antagonist, cruel and uncompromising, the enemy of a good yarn, and lofty idealism!

The sheep were grazing for little over two months. The plan was that they would graze both the cover crop, and the grass-weeds — namely rye-grass. The plan was that they would also add some needed biological life back to the soil. They did a pretty good job in truth. Much to my satisfaction, they had a particular taste for charlock, an arable weed that is relatively easy to kill within a conventional system, but is a bit trickier when farming without the totality of modern herbicides. Throughout their stay, they only escaped once, with minimal damage. The sheep left on March 17th, straight to Ashford market. Some to be slaughtered, some to be fattened up elsewhere. A great success. Thank you, Paul the sheep guy!

On March 18th, whilst I guiltily worked at my other job, my uncle started ploughing. It’s a slow job, made slower by the heavy dirt of Fellin Pitts. March 19th, with only a few hectares left, the tractor went bang. This was the first of the bad omens. The rear differential exploded under the pressure of pulling the plough, blowing a hole through the axel. The tractor was left stranded in the field over the next few days.

Elsewhere on the farm, there was lots of spring planting. The very wet winter of 2024 meant that many hectares had been left unplanted. It had been a tiring few weeks of long days, playing catch-up. On the final block of land before Fellin Pitts, both the top-down and the power-harrow broke: a ram on the former, the gear-box on the latter. Every time I drove to and from the field, something else seemed to have broken, and Dad was angrier and angrier.

((As an aside, let me briefly explain the various steps necessary to plant a crop in modern arable farming. First, either the plough or the top-down is pulled behind a tractor. These machines turn over the top layer of soil, each at a different depth, burying and disturbing the top layer of debris, to create a nice clean seed-bed. Next is the power-harrow. This noisy, thirsty machine mechanically breaks up the already cultivated soil into smaller pieces, small enough that the drill can pass through. The drill, again pulled by an enormous tractor, is the machine that plants the seed, arguably the most necessary of the lot. Finally, the ground is consolidated by a massive set of rolls: heavy weights are dragged behind the tractor to ensure a good seed-soil contact. This system is true of both organic and conventional systems. In truth, as I write all of the above, I’m slightly horrified at the extent of this carbon decadence. So much bloody oil is burnt in the process, sustainable farming or otherwise.))

We borrowed a neighbours power-harrow to finish the job of following the plough in Fellin Pitts. After about 8 hours, half of the job, another tractor went bang. The water-coolant broke, snapping the belt that drove the cooling fan. Half of half a job. Image below.

This was on the afternoon of Friday the 21st. Of the planned 20 hectares, about 5 were ready to be drilled. Dad finished this, I rolled behind him, and we called it a day. Nothing left for us to do, except to cry. This had been literally years of work to get to the point of putting this seed in the ground, and at this critical moment, it seemed that everything wanted to go wrong. The afternoon was spent bringing the corpses of machines back to the yard, and bringing all the unused seed back to the shed.

Saturday we were all too exhausted to do much. Dad changed the lights on his tractor, and I slept throughout the day. Sunday was much the same. Monday morning, I went back to school. GCSE chemistry felt a bit ridiculous, knowing that there was still so much to do at home, and that there was so little that I could do. Dad and his brother set about fixing what they could, and botching what they couldn’t. A few days in my absence, and it was more or less done. The one remaining tractor finished the ploughing, the power-harrowing, and then drilled the rest. By Wednesday evening (the 26th), everything was safely in the ground.

And I wasn’t bloody there!

And the rain finally came for you!