A cover crop of stubble turnips, black oats, and vetch, grazed by sheep; top-downed, drilled with a Mariagertoba spring-wheat population, under-sowed with white clover and yellow trefoil; harvested, maybe grazed by sheep again, back to a cover crop.

Wait slow down. What’s going on? That’s a lot of detail.

That’s the plan for the first year at Fellin Pitts.

Can you explain it in a bit more detail? To start, what is a “cover crop”?

A cover crop is a mixture of plants that are chosen to cover the ground during the winter months. They’re not grown as a “cash crop” — the plants won’t be harvested and sold — but rather, they’re grown to benefit the soil. It’s a practice often associated with regenerative agriculture. One of the key principles of regen-ag is to maintain live roots for as much of the year as possible, as it is these live roots that feed the soil ecosystem. Always have something growing!

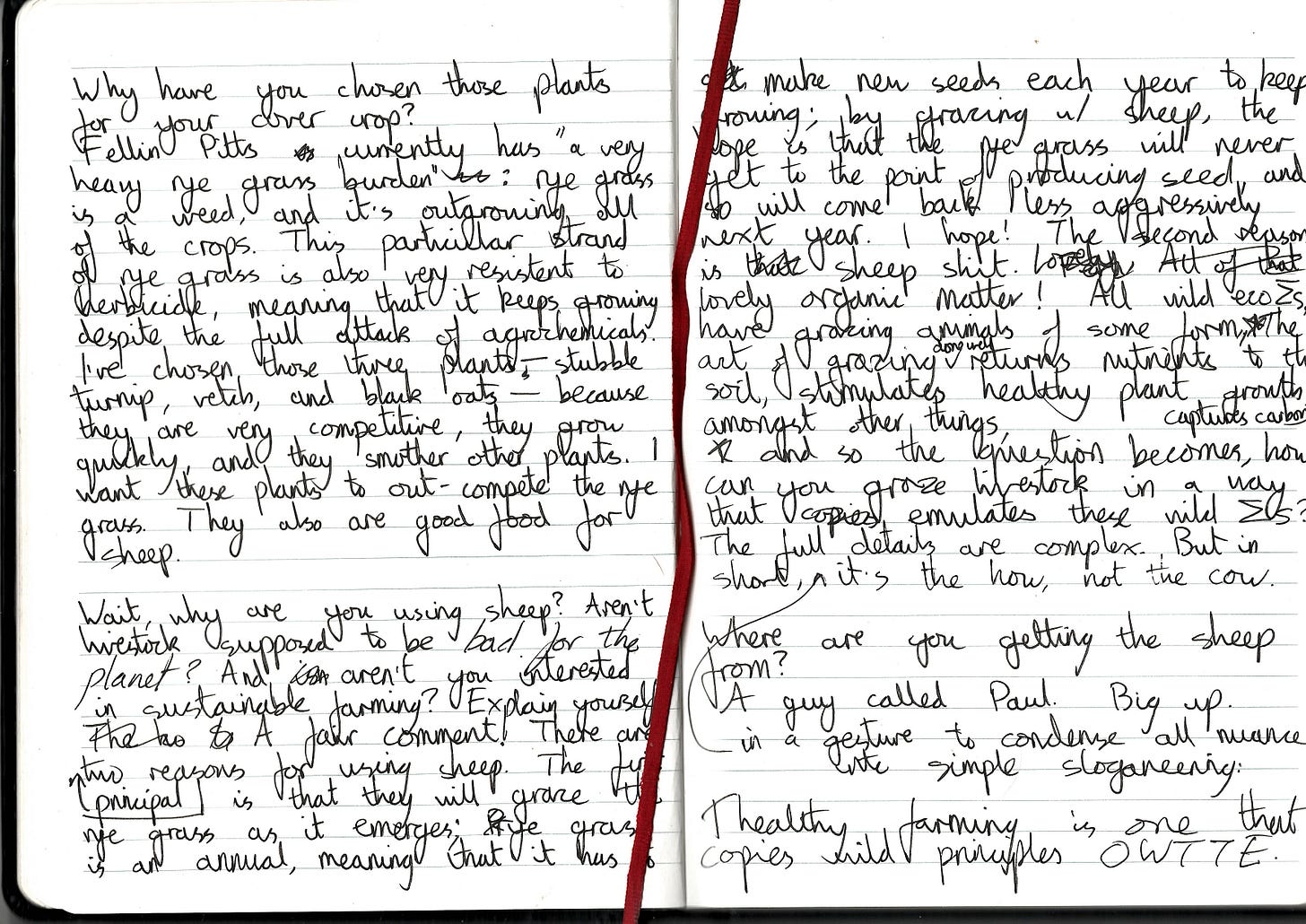

Why have you chosen those specific plants for the cover crop?

To use the jargon, Fellin Pitts currently has “a very heavy rye-grass burden”: rye grass is a weed, there’s a lot of it, and it’s outgrowing the things that I would like to grow.

Wiat but like isn’t a “weed” just a… *rips cloud* like… social construct? Liek when you break it down, what even is a weed? It’s just some dude saying that you’re a bad plant and you’re a good little plant, right? That’s pretty out of sight if you ask me, man.

Thanks for that, yes, wonderfully insightful. But as I was saying, this particular strand of rye grass is also very resistant to herbicides, meaning that it keeps growing despite the full attack of agrochemicals. I’ve chosen those three plants — turnip, vetch, and oats — because they are very competitive, they grow quickly, and they smother other plants. I want these plants to out-compete the rye grass. I want to use biological means of controlling the rye grass, not chemical. These plants are also a good food source for sheep.

Why are you using sheep? Aren’t livestock supposed to be bad for the planet? And aren’t you supposed to be interested in sustainable farming? Explain yourself!

A fair comment. There are two main reasons for using sheep. The first is that they will graze the rye grass. They are a key part of the biological weed control. Rye grass is an annual plant, meaning that it has to make new seeds each year to keep growing (one mature plant makes something like 7,000 viable seeds per year); by grazing with sheep, the hope is that the rye grass will never get to the point of producing seed, because it never reaches maturity. Hopefully, it will come back less aggressively in the following year. I hope! The second reason is sheep shit. Lovely, lovely sheep shit. Think of all of that organic matter! In a few more words, all wild terrestrial ecosystems have grazing animals of some form. And so, from a farming perspective, the question is: how can you graze livestock in a way that emulates these wild systems? Truly sustainable farming, in my eyes, can be seen as an attempt to learn from these wild systems, and to let them inform agricultural practices. Grazing done well returns bio-available nutrients to the soil, stimulates healthy plant growth, captures carbon in the soil, amongst other things. The reality of livestock farming, and whether they are “good” or “bad” for the planet, is complex. So, to reduce this complexity to simple sloganeering: it’s the how, not the cow.

Where are you getting the sheep from?

A guy called Paul. Big up Paul the sheep guy.

So what comes next?

The sheep will graze the cover crop over the winter. Towards the end of February, the sheep will leave to greener pastures (cheers Paul), and then the ground will be prepared, using a machine called a top-down, for planting wheat.

What’s this Maria-ger-ber-whats-it-called? What’s that all about?

Mariagertoba is a population of heritage wheat. It is a population bred by a Danish wheat farmer. I’m interested in growing it because bakers like it, because it works well in organic systems, and because it works well as a spring variety. This means that I can plant it some time in late February//early March, and it will be ready to harvest by August. It will fit well with the cover-crop-sheep combo.

And what about the white clover and yellow trefoil?

White clover and yellow trefoil are both legumes, which are part of the Fabaceae family. To quote someone who knows more than me: “legumes have evolved a unique ability to partner with soil bacteria to convert atmospheric nitrogen gas into a plant-useable form of nitrogen”. Therefore, the legumes will fix nitrogen for the wheat to use as it grows, and so replace the need for the synthetic nitrogen of the Haber-Bosch process. Another example of biological farming, rather than chemical. Furthermore, growing legumes alongside the wheat creates more plant diversity, and so is a closer copy of wild grass systems. White clover and yellow trefoil are interesting specifically because they grow outwards, not upwards: they smother. The plan is to plant them after the wheat is well established, and use them to smother any remaining rye-grass. This is a hard balance to get right: the legumes can also smother the wheat, and they can also feed nitrogen to the rye grass. The hope is that there is an understory of legumes, whilst the overstory is dominated by tall heritage wheat. That’s the theory at least.

Can the sheep also graze this too? Why do you get rid of the sheep?

Yes and no. They can graze this, but I don’t want them to. After they’ve done all of their good work on the cover-crop, I want to give the ground a break from livestock for a little bit, and let the wheat grow nice and tall, so that it makes seed, so that I have something to harvest. After the harvest, I may well introduce sheep again, to graze off the excess legumes, before starting the cycle again.

Who is buying the wheat?

Gilchesters organics. They are a small company that grow interesting grain, and mill it themselves. You can buy from them directly! I met them earlier this year. They’re great people. Their promise to me was “you grow it, we’ll buy it”, for which I am immensely grateful: it has given me the confidence and the ability to get this project off the ground, to start growing these interesting and niche grains. They will also be able to mill the flour into smaller bags, so that I can sell it directly to those interested. Stay tuned…

What are the biggest challenges going to be?

Rye grass! It is very competitive, and has ruined many crops of my father. It also has the annoying habit of growing very tall, lodging, and then dragging down the rest of the crop. Another big challenge is that Fellin Pitts tends to be very wet in the winter, and so it might be difficult to plant anything in February or March, as the ground becomes a big gloopy mess. Pray for good weather! Finally, Dad is cynical that this will work: it will be a challenge to keep the faith in a new and untried system, amongst the background of doubt.

Why does any of this stuff really matter though? What’s the bigger picture?

There are layers to this question, so let me try to answer upwards. As I’ve mentioned a few times throughout, this is a biological approach to farming, rather than a chemical one. My hope, in that case, is that biological life will fare better. I’ll be planting habitat for bugs, birds, and bees amongst the growing area, to encourage natural predators to pests. As part of growing organically, there will be no pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides, and so the various creatures targeted by these -cides will be happier, or at least more abundant. Thanks to Paul (big up), this will be the first time any livestock has been on the farm in at least 50 years, if not more. Who knows what that will do! An end to the chemical convenience of nitrogen in a bottle, and the destruction on the road to this convenience. By growing Mariagertoba, it will be the first time that bread-quality wheat has been grown here in decades, and so I’ll avoid the waste of grain as livestock feed. It should also be bloody delicious as well. Real bread! I’ll be moving away from anonymous global grain commodity markets, and moving towards real people. Know where your food comes from! If I’m lucky, and I manage the soil well, I may capture some atmospheric carbon and increase my soil organic matter. I’ll also have the privilege to work alongside my family — there isn’t much today that allows for that. I’ll also learn a lot: I have a head full of ideas, and it’ll be very exciting to see what works. It should be a lot of fun!

Wow! That sounds great!! Is there anything I can do to get involved?

Yes absolutely! The first, and most obvious, thing is to buy my flour when it’s ready. If all goes to plan, I’ll have lots of bags of flour looking for a new home this time next year. The second is that I will almost invariably host a big gathering in spring, in the name of pulling out rye grass. A day of fun, in the Kentish sun, rogueing the undesirable one. Plus there will be beers and barbecue. Come join!

Glossary

Lodging — when a plant grows too tall, and snaps under its own weight.

Rogueing — an old-timey word for hand pulling weeds from a field.

Soil organic matter — the organic matter component of soil, consisting of plant and animal detritus at various stages of decomposition, cells and tissues of soil microbes, and substances that soil microbes synthesize. (From Wikipedia.)

Spring variety — a variety of crop that works well when planted at the beginning of spring. This term is used in contradistinction to winter varieties, which, despite their name, are planted in autumn. Confusing, I know.

Well done with this plan - so exciting! Best of luck, go prove your Dad wrong! 😉

Weed-pulling and bread baking!!???? Be still my beating heart