To the mill

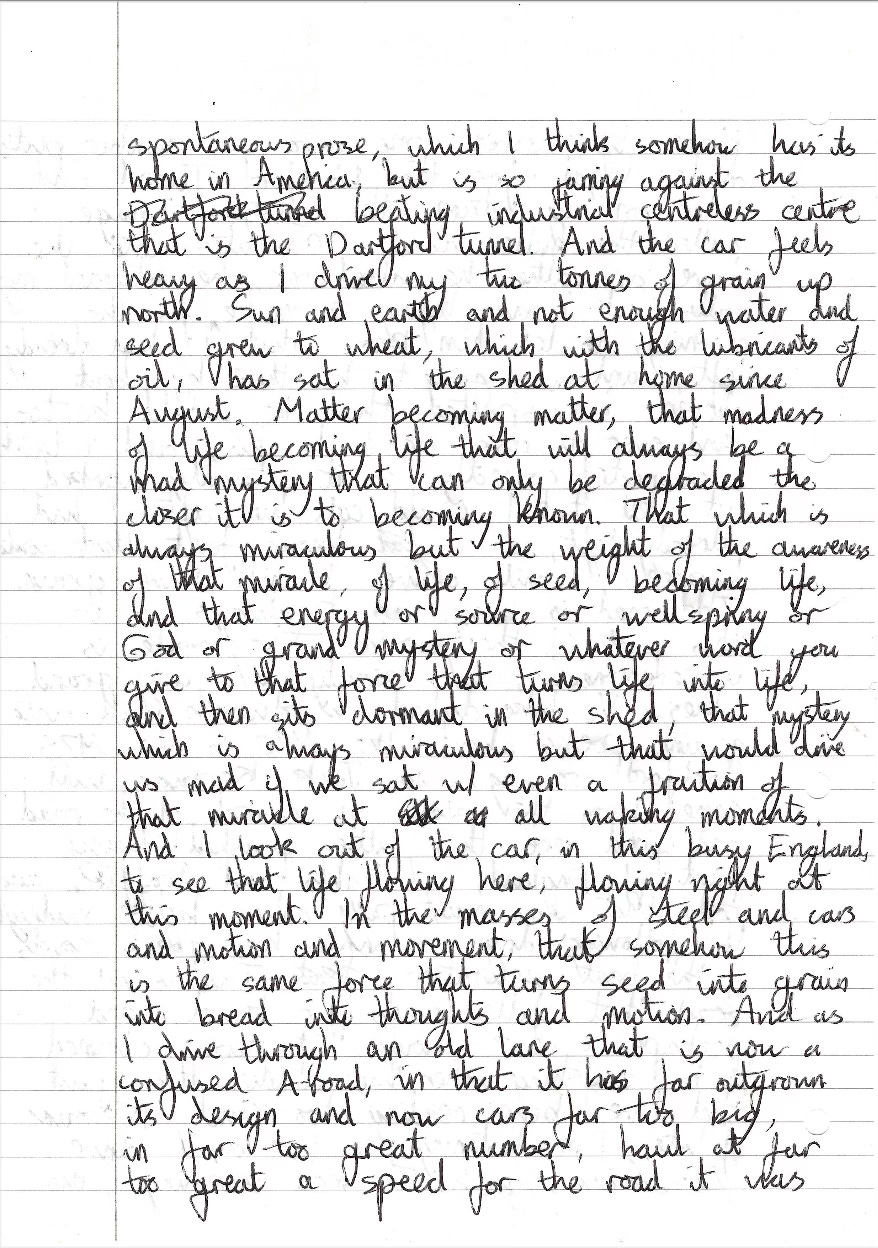

The first load of grain arrived at the mill today. I say arrived, more accurately the first load was delivered, by me, yours truly. I had organised a grain haulage truck to move it, or I thought I’d organised it. It was a game of disorganised whispers between my dad and me and the guy from the haulage company. I said that the mill wanted it Thursday, as in yesterday, back two weeks ago, and Dad said that the haulage guy, someone called David, could do it, someone who Dad had done a big favour for this last summer, lending him a tractor for nearly two months after his storage shed, Dave’s, caught fire. Some rape seed oil, apparently now bred for higher oil content to keep the supermarkets happy, spontaneously set fire, combusted, in the heat of a summer day. Boom. Some crazy number of tonnes, a crazy amount of oil, flammable no doubt so that we can all use it to fry with at home, I want to say 500 tonnes of this stuff. Anyway, once the fire was all put out, there was the burnt charred crap that had no use to anyone anymore, not even cows would eat it. Dad leant them a tractor and a machine called, no word of a lie, a sucker-blower, precisely because it sucks crap from somewhere and blows it someplace else. Dave borrowed this for the summer to clean out the burnt remains at the bottom of his burnt storage pits. Insurance paid for the whole lot, so I’m told. Anyway, Dad asked Dave to shift some grain for me on Thursday of this week, to make the 40 mile drive, give or take, to the mill. Dave said yes, sort of, then radio silence, then no actually not Thursday, it might be Friday, or maybe some time next week. The mill had more or less run out of grain, and so needed mine. Needed it ideally yesterday. I felt as though somehow this was my mistake, that I didn’t organise the haulage in time or wasn’t clear or whatever. And this was the first time the mill was getting any of the grain I grew, and so I didn’t want to set the precedent, create the expectation, that I was one of those guys who couldn’t organise haulage in time — one of those useless academic sort of people who can philosophise perpetually on the brokenness of industrialised agriculture, and writes reams of junk to live online in some corner of the internet that gathers a particular flavour of digital dust just to prove my philosophical philosophising, but couldn’t organise haulage. Couldn’t move grain from A to B, not on time at least. This was a bad precedent to set, and I wasn’t busy (tremendously), and I knew that the millers needed the grain, or least a small amount to get them through to next week until Dave could haul the rest of the grain, and they, the millers, had done so much to help me in the last year that a short morning drive felt like a small price to pay. Or not even a price to pay, but it would be a day well spent. And so I bagged two tonnes of grain into three bags, one in the back of the pickup, two in a trailer, and drove the grain there myself. Ratchet strapped in place, tyres given some extra air, number plates made legal for the Dartford Tunnel and later, on my return, the Dartford Bridge. I called the miller about 30 minutes into the drive, or rather he called me, he returned my calls that I was trying to make for the morning, to let him know that I had already left, and was going to be there by about eleven. I suspected that he would be too kind ever to ask me to do this, and I think I suspected correctly, so it worked well that I could call him after I had left, as a known fact that would happen. I will arrive. I will have grain. The road is busy, as it always is in this part of the world. The route is unceremonious, without beauty, without any grand skies or dramatic hills. No Lake District Wordsworth will write quaint poems about the M20 to the M25 Dartford crossing, no Jack Kerouac will come from the States in search of the road and find here, this little squashed busy part of England, with lights and traffic and tolls that you must pay online before midnight the following day, to write his great novels of the Beat generation. This is not the road that fills souls for travel, and perhaps it never should, it never claimed to be anything other than utility. It’s just that I’ve been reading too much Kerouac of late, I’m listening to him as I drive. Desolation Angels. The mad searching of his spontaneous prose, which I think somehow has its home in America but is so jarring against the beating industrial centreless centre that is the Dartford tunnel. And the car feels heavy as I drive my two tonnes of grain up north. Sun and earth and not enough water and seed grew to wheat, which, thanks to the lubricants of steel and oil, has sat in the shed at home since August. Matter becoming matter, that madness of life becoming life that will always be a mad mystery that can only be degraded the closer it is to becoming known. That which is always miraculous but the weight of the awareness of that miracle — of life becoming life, of seed becoming seed — and that energy or source or wellspring or God or grand mystery or whatever word you give to that force that turns life into life, and then sits dormant in the shed for four months, that mystery which is always miraculous but that would drive us mad if we sat with even a fraction of that miracle at all (or any) waking moments. And I look out of the car as I drive, in this busy England, to see that same force flowing here, flowing right at this moment. In the masses of steel and cars and motion and movement, that somehow this is the same force that turns seed into grain into bread into thoughts into motion again. It is always right here. And as I drive through an old lane that is now a confused A-road — confused insofar as it has far outgrown its birth and now cars far too big, in far too great a number, haul at far too great a speed for the road it was when it was born — as I drive here a bird, a big falcon of some sorts thrills itself in a kamikaze mission to fly across traffic in the gap that momentarily appears, flying no more than a foot above the road, narrowly missing both me and the truck that is heading the other way. And I think is to for the thrill? Is it a moment of panic? Is it chasing another smaller bird, searching for lunch? But it’s gone, and I'm gone to it, and I keep driving. It’s impossible to stop quickly with these two tonnes of grain, not that I would have stopped otherwise. The madness of the bird that nearly kills itself seemingly only to have nearly killed itself. And the confused A-road becomes the M20, which becomes the M25, which takes me under the Thames soon enough. And when, later in the day, I return, I’m taken over the Thames, I see the madness of insanity that is the sprawling fleet of Amazon delivery trucks, hundreds and hundred of these blue trucks, almost the pure blue of summer sky blue. All of these trucks plugged into the enormous, unfathomable, unholy monster that is the Amazon Fulfilment Centre. Some great brain, some great force, some great mind that hums and thrums and pulls at pushes and strives towards something. It is the same force that makes grain grow, that turns life into life, that much I know for sure, but somehow this force, in this manifestation, is untethered here. And I don’t even, I can’t even hate it. Not that I can say that that brain thinks and moves in my name, that those trucks are for me or because of me. But I can’t say that that energy or force doesn’t at least move slightly because of me, and so how can I hate it? And what does it even mean to hate something like this? And I laugh to myself as I get to the other side of the Thames. That I’m growing grains, reviving old heritage grains, growing organically, regeneratively, with nature, building a sense of home and beauty, and so much of it, my work, at least at its naively idealistic best, tries to move against this madness. And yet I’m here. Driving two tonnes of grain to the millers over the Dartford crossing that towers over Amazon and Sainsbury’s, and has London’s skyline in the distance, and that the only time you can be on this bridge, watching all of this madness beneath you, is when you yourself are driving at 50 miles per hour. That you yourself can’t be still amongst this motion that sprawls underneath feels wonderful, somehow, or at least inevitable and therefore brilliant. And I laugh that despite all of the labels I give myself, and the rehashed stories of being an organic farmer and a teacher and whatever else I have to say to give me a brand that apparently I never wanted but somehow always needed and so has arrived to me nevertheless, that despite all the fake pretending of novelty, that what I’m doing today is as old as the hills. That taking grain to the mill is as old as the oldest stories. There’s nothing remotely modern in how life becoming life flows through me to turn grain into flour into bread. But I think that my ancestors would laugh, or baulk in horror, that I have to travel so far for the mill. I tell myself, once again, repetitively, how mad this system of such agricultural specialisation is, how every town would have had a windmill and now they’re all commuter homes for Londoners or cute quirky weekend getaways on Airbnb. And so I look for a windmill on the side of the road. I want to find one to justify my repetitive repetitions, but the world is never so simple. Never so obliging. The grand life force has a way of slipping my grip whenever I try to pin it down too firmly, whenever I command that there must be a vacant windmill on what is now the side of the M11, vacant to confirm me in in theories of rural decline and the reign of money. But there is no such windmill and so I continue to the actual mill. There is a red kite hovering over the road, looking for something. I don’t see the bird for long enough to know if it’s successful. Hunting over the M11, think of the noise! And the M11 becomes the A-something, which becomes the B-something, which becomes the farm with the mill. They’re pleased to see me, the millers, grateful for the grain. In our excitement, we empty all of the grain into their silo without weighing it, and so I can only guess that it was two tonnes spread over three bags, maybe two and a bit. I haven’t seen the millers since the summer, just before harvest, and their place has changed a lot since then, there is the cold of December morning now, the feeling of the earth falling asleep. They show me some wheat in the ground, and fields of cover crops and test plots. Since I saw them last, one of them has had his first child, and the other has become engaged. Life becomes life. They take me to a pub, buy me lunch and beers to say thank you for the grain. That grain that is now loaded into the silos, and that by the time that I load back into the car, make the drive back, from B-something to A-something to M11 to M25 to M25 to A-something to home, by the time I get home some of that grain will have already become flour. And life becomes life.

The rest of the grain will be milled over the next few months. I want to find a way for at least some of the people reading these words to eat the bread that was the flour that was the grains that I have helped to grow. If you are interested in becoming one of those people, now is a good time to let me know. Write below or send me a message or something. Support your local farm!

“I was one of those guys who couldn’t organise haulage in time” the worst kind of people

Beginning is hilarious