Sometimes Nature Sucks

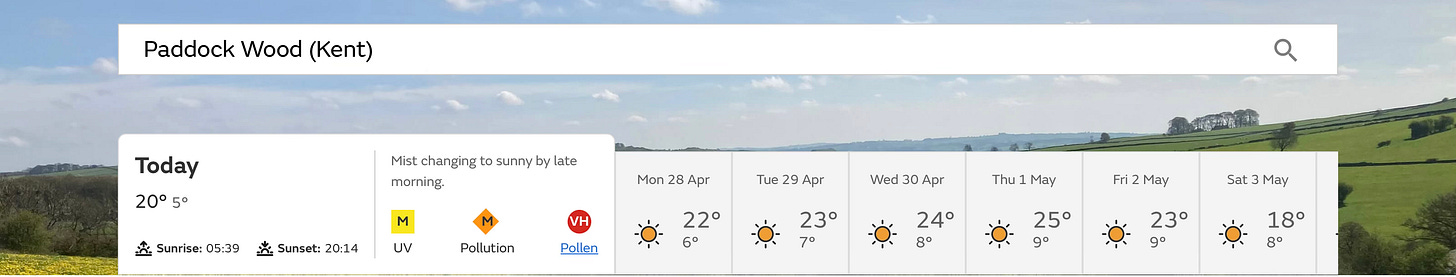

It was a wet autumn, and a wet winter. From September until February, the longest stretch without any rain here was eight days. We barely managed to finish half of the winter planting, it was too wet for the machinery to drive through the fields. Six months of solid rain. Then a switch flicked. Since March, there have been three days of rain, total. Normally, we get about 50mm of rain in March. Last year we got 80mm. This year, we got 3mm. I wish I was exaggerating

We planted Fellin Pitts in mid-March. Then it didn’t rain. The seed sat in the ground, waiting. It won’t start germinating unless there’s enough moisture. A few brave seeds tried. Most waited. The crows moved in. Every time I visit, there are at least two hundred of them. Black sinister looking bastards. I get why they were harbingers of death. Crows seem to have a taste for newly germinated wheat; they seem to wait for the chemical change of turning sugars into growth. And since it’s been so dry, and germination so slow, they’ve done a good job of keeping on top of things. Keeping that germination in check.

We got the first dose of rain nearly a month after planting, and a second a week after that. 20mm in total. All of this is to say is that it looks a bit patchy. On the good dirt, it looks good; on the shit dirt, it looks, well, a bit shit.

Sometimes nature sucks.

It should be okay. We’ll have something to cut. I have faith that these old varieties will prove their worth. A dry spring is not new, and these varieties have been passed on for a reason. And I can honestly say that we did everything right. To borrow a phrase from Dad, we didn’t miss a trick. I can’t control the weather, and I’m way too young in this game to start resenting the rain.

But there’s a reason that our ancestors saw gods everywhere, fasted in their honour, personified the crows, left offerings, prayed to Lady Fortuna, celebrated harvests. There’s a reason they didn’t waste food. There’s a reason that every week in the Orthodox liturgy, we pray for “an abundance of the fruits of the earth”. It’s not that our ancestors were backwards, or irrational, or superstitious: these acts gave them something to do when it didn’t rain, someone to ask for help, something to do other than frantically refreshing the MetOffice ten times a day.

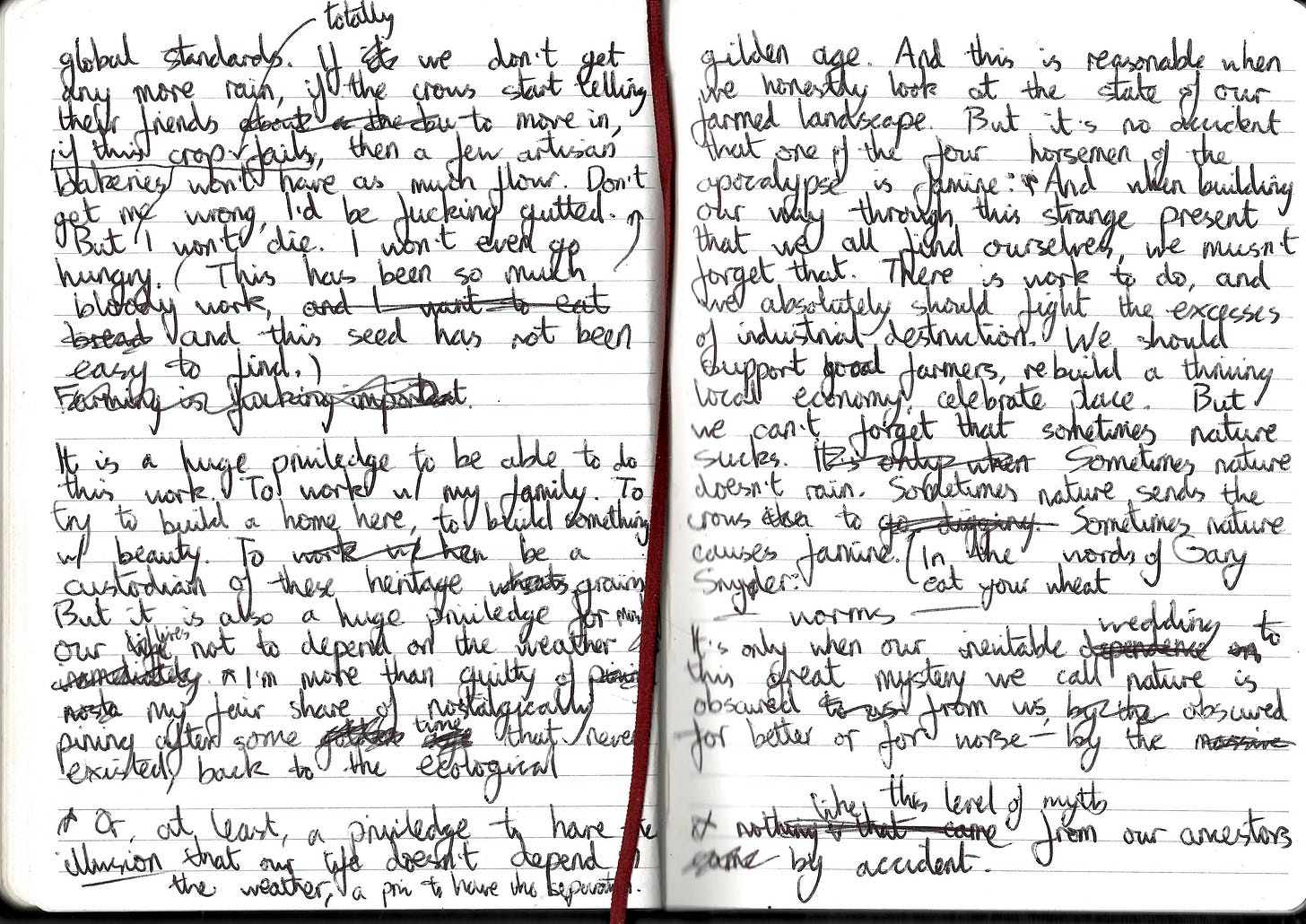

I’ve never known hunger. Not proper hunger, not weeks at a time hunger. I imagine it’s the same for most people reading these words. That is a huge privilege, both by historical and global standards. If we don’t get any more rain, if the crows start telling their friends to move in, if this crop totally fails, then a few artisan bakeries won’t have as much flour. Don’t get me wrong, I’d be fucking gutted. This has been so much work, and this seed has not been easy to find. But, if this crop totally fails, I won’t die. I won’t even go hungry.

It’s a huge privilege to be able to do this work. To work with my family. To try to build a home here, to build something with beauty. To be a custodian of these heritage grains. But it is also a huge privilege for most of our lives not to depend so intimately on the vagaries of the weather. Or, at least, a privilege to have the illusion that our life doesn’t depend on the weather.

I’m more than guilty of my fair-share of pining nostalgically for a time that never existed. Back to the ecological gilded age. Back to the time where everyone knew their farmer, and we all ate seasonally, locally. The peasants diet. Back to the time where our landscape wasn’t dominated by single cultivars, and when our fields weren't ecological deserts. Back to the time when you can swim in the river without fear of nitrogen leaching. And this nostalgia, I maintain, is reasonable when we honestly look at the state of our farmed landscape. But it is no accident that one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse is famine: nothing like that came from our ancestors by accident. And when building our way through this strange present that we all find ourselves, we mustn’t forget that.

There is work to do, and we absolutely should fight the excesses of industrial destruction. We should support good farmers, rebuild local economies, celebrate place. But we can’t forget, in that work, that sometimes nature sucks. Sometimes nature doesn’t rain. Sometimes nature sends the crows. Sometimes nature sends one of the four horsemen. In the words of Gary Snyder:

The other side of the “sacred” is the sight of your beloved in the underworld, dripping with maggots.

It’s only when our inevitable wedding to this great mystery we call nature is obscured from us, obscured — for better or for worse — by the massive sprawling industrial food system, it’s only then that we can “love nature” in its entirety. It’s only when we are fed, by “good farmers” or otherwise, that we can “love nature” exclusively. Yes, we have always known how to love a place, to be awed and humbled, to venerate and revere. But our ancestors knew much more than just love. Sometimes nature sucks. God speed the plough!